WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY

Biodiversity comes from two words; biological and diversity. It is a term that describes the variability of living things. Living things consist of bacteria; single-celled organisms such as Amoeba, Paramecium, algae and others; fungi and mushrooms; plants; animals and human beings. Living things that occupy planet earth may be found in the terrestrial and/or aquatic ecosystem. Some living things like birds and insects, those with wings, may even be found in the atmosphere. The variability or diversity can be considered at three levels – genetic, species and ecosystem.

Genetic variation would involve variation of the genetic make-up of individuals within one species. A practical example as shown in Fig. 1 is that despite cauliflower, cabbage and broccoli are categorised as one species Brassica oleracea, they have different shape, texture and colour. Besides that, other variation of cabbage may come in different shapes – the more common rounded cabbage and the sweet cabbage which is longish. They even come in different colours too like whitish green and purple (Fig. 2).

The common cabbage is whitish green (left), whereas the less common red/blue kraut has purple leaves (right).

For a layman, biodiversity is easiest understood by looking at the level of species diversity. As an example, among butterflies (order: Lepidoptera; suborder: Rhopalocera) groups, there is a family called swallow-tails (family: Papilionidae) which have several species. Five different species of Papilionidae are shown in Fig 3. Between the species one could differentiate the shapes and patterns of the wings.

As for plants, a coconut tree (species Cocos nucifera) is different from an oil palm tree (species Elaeis guineensis) (Fig. 4). Although they are from one family known as the palms (Palmae) and both tend to have a straight trunk without branches, oil palm has numerous small fruits in a bunch while the coconut tree’s fruits are much bigger and fewer.

At a more interactive complex level, diversity could be seen in the various ecosystems. In this context, composition of biodiversity occupying a specific ecosystem differs which will produce different kinds of interactions. Interactions between organisms occupying an ecosystem produce equilibrium and these interactions are specific to the ecosystem. Comparatively, the desert ecosystem has very few trees and animals, thus interactions are few. In the species-rich tropical rainforest (Fig. 5) however, there are uncountable interactions between the different species producing a more stable equilibrium that typifies the ecosystem. Thus, at this level biodiversity is much involved with relationships and interactions. An example of this ecological interaction is the predator-prey relationship. These are organisms (predator such as an owl) that feed on other animals (prey such as rats). Predator-prey relationship can happen in an oil palm plantation habitat or a forest habitat.

In the tropics, there are several other kinds of ecosystems besides the tropical rainforest. One example is the mangrove (Fig 6). In order to adapt to a coastal environment, mangrove plants have specialised physiological mechanisms to enable them to live in salt water. In this ecosystem, the species diversity is poorer with the family Rhizophoraceae being predominant amongst the trees.[1] This poorer plant composition in turn supports lesser animal diversity.

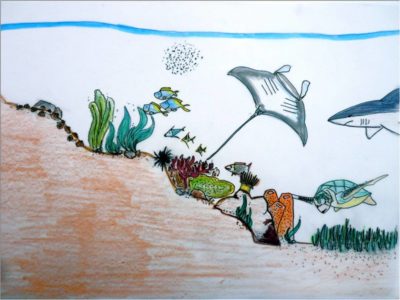

The marine ecosystem in the tropics supports a different array of organisms and thus produces different kinds of interactions. As shown on Fig. 7, sea weeds are normally found nearer to shore, whereas sea grasses are found further and deeper. Different organisms will feed on these marine plants. Most marine animals will feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton. The marine organisms will interact in various ways, producing stability to the marine ecosystem.

The definition by the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1991 (Fig. 8) is most suitable to encompass all kinds of varieties of life forms which defined biodiversity as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystem.” There are three main objectives of the convention namely conservation of genetic resources of the world (biodiversity), sustainable use of genetic resources and equitable sharing of the benefits derived from the use of genetic resources. It has 41 articles and some issues outlined in some articles are of concerned to Malaysia. These include sovereignty issues, traditional knowledge and access and benefit sharing.

DISTRIBUTION OF BIODIVERSITY

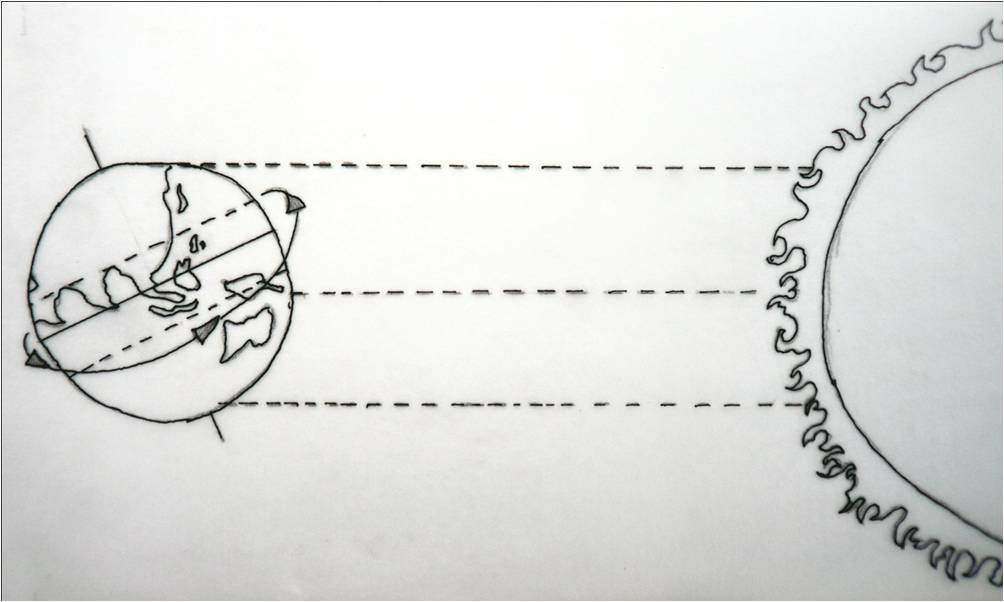

Biodiversity is not equally distributed throughout the world. The basis for diversity distribution is much governed by the availability of energy and food for organisms to live on. For plants, the availability of solar radiation is critical to their survival because plants need energy from the sun for photosynthesis and make their own food. Thus, for areas in the world that receives most sunlight for longer period of time and have enough water will support more plants, not only in number of individuals but also in terms of its species diversity. Figure 9 shows the tropical region being more exposed to the solar radiation, and receiving at least a 12-hour sunshine. In the temperate region, due to the inclination of the Earth, the northern and southern hemispheres are less exposed to sunshine and the various climatic seasons (summer, autumn, winter and spring), the length of the photoperiod (the span of time an area is exposed to sunshine) varies tremendously. For example, the United Kingdom will receive about 6 hours of sunshine during winter and 18 hours, during summer, whereas in Malaysia we have a constant photoperiod of about 12-hour daylight, all year round.

Plants constitute food for most animals. Therefore, the number of plant species that live within a given area will determine the number of species of animals that could survive in that area. Thus, the more diverse the plant species, the more diverse will the animal species be. On this basis, areas in the tropical region with diverse plant species will also support larger number of animal species.

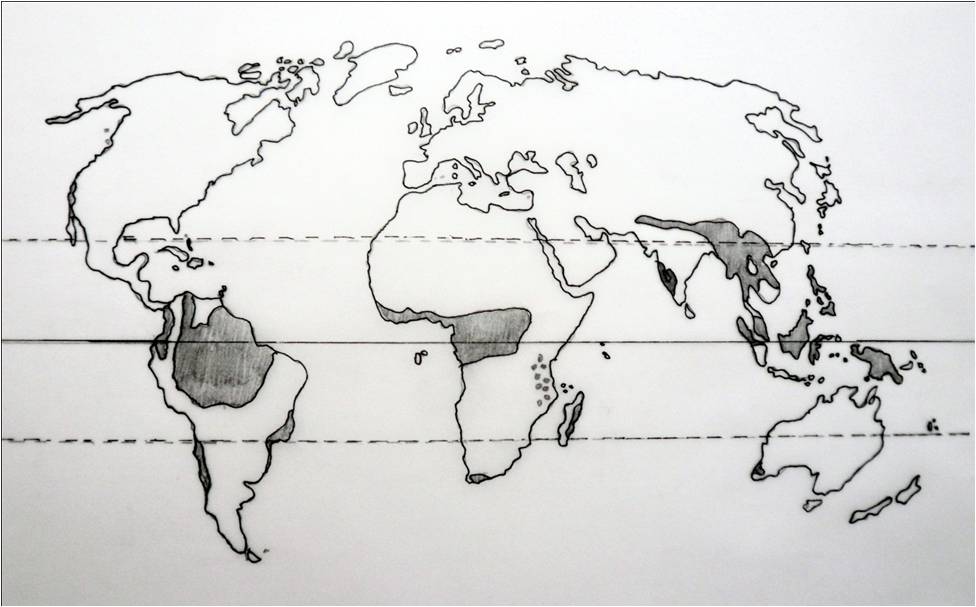

Due to this fact, tropical region (areas between 23°N and 23°S), lying along the equator is rich in biodiversity. One reads of the richness of the huge Amazon forest of Brazil, and perhaps watches documentaries on the vastness of the Congo forest in Africa. The forest of Southeast Asia, lying along the equator is also well documented for its rich biodiversity. Altogether, the size of tropical rainforest of the world is about 7% of the global land surface. It is said to be harbouring more than 50% of the global biodiversity. Figure 10 shows the locations of the tropical rainforests. According to Whitmore 1998,[1] the largest block is the American or neo-tropical rainforests of about half of the global total, 4 x 106 km2 in area (including the Amazon), followed by the eastern tropics, estimated to cover 2.5 x 106 km2 (in Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, southern Thailand, Vietnam and Brunei). African tropical rainforests (Congo, Ghana, Guinea, Cameroon and Gabon) is the smallest block of 1.8 x 106 km2. There is a patch in India (the Western Ghat), the whole of Papua New Guinea and northern tip of Australia.

THE GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY

In the world, there are estimated 1.75 million named organisms. The breakdown of biodiversity given by Gleich et al, (2000) [4] quoting World Conservation Monitoring Centre 1992 (WCMC) [5] is as represented in Table 1. It is clear that insect is very diverse with about 950,000 species. Quoting from Erwin for his work using the fogging machine raised into the canopy, Mitchell 1986 estimated that there are 30 million species of insects in the world.[6] Wilson (1992) [7] however, worked on a figure of 10 million species.

There are five groups of organisms with human being the sixth. Among the plant groups, vascular plant had been well studied. There are about 270,000 species of vascular plants (Table 1). Among the animal groups, mammal has been well studied with about 4,630 species recorded in the world. Least studied groups were invertebrates and microbes as they are very tiny and may not be seen with naked eyes.

Table 1 : A table to show biodiversity of the world.[4]

| Estimated numbers of still unknown species | 10,000,000 – 200,000,000 |

| Number of all known species | 1,750,000 |

| Insects | 950,000 |

| Plants | 270,000 |

| Spiders | 75,000 |

| Mollusks | 70,000 |

| Crabs | 40,000 |

| Fish | 25,000 |

| Birds | 9,950 |

| Reptiles | 7,400 |

| Amphibians | 4,950 |

| Mammals | 4,630 |

As for its distribution, most biodiversity is found in countries along the equator. The tropical rainforest account for about 7% of the global landmass, yet it is estimated to contain about 50% of the global biodiversity. Figure 10 shows the locations of tropical rainforests. In the tropical rainforest, it is estimated that almost half the global biodiversity is at the canopy.[8] Another diverse ecosystem is the marine ecosystem. Both the canopy and the deep oceans are not easy to access and as such not much discovery could be made.

Ecosystems that have poor biodiversity are the climatically extreme areas such as the cold polar region and the hot and arid deserts. Neither plants nor animals could live in extreme climatic conditions. Some microbe however, could.

Cox, 1997 [9] describes biodiversity hotspots as areas where there is unusual concentration of species, and usually of endemic species. He indicated that they tend to be located where bio-geographic isolation has favoured speciation and adaptive radiation over a long period of evolutionary time; where bio-geographic connections have mixed the biotas of different continents, or perhaps where long continuity of favourable environmental conditions has allowed evolution to proceed with few setbacks for a long period of geological time. Northern Borneo (Sabah) is one of the terrestrial biodiversity hotspots.

ENDEMISM

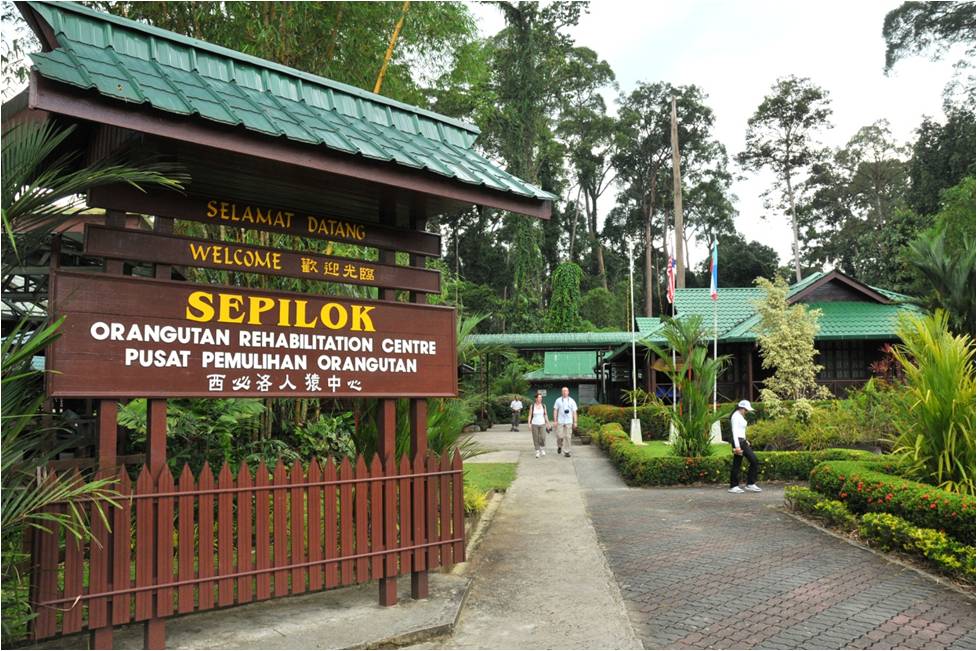

Variations in climate for the different locations on this planet will support different kinds of plants and animals. Through the long evolutionary processes and isolation, some animals and plants are only found in specific geographical areas and not elsewhere in this world. As an example, the Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus; Fig. 11) now could only be found in Borneo and Sumatra (in the wild) which we termed the Orangutan as endemic to Borneo and Sumatra. Another example is the proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus; Fig. 12), that can only be found in Borneo.

There is a slight difference in the endemism of these two species. At one time, Orangutan was found also to be distributed from south China to Borneo, Java and Sumatra. However, due to human consumption and keeping them as pets, they become extinct in some areas. Due to existence of some forests in Borneo and Sumatra, followed by public awareness and recent conservation efforts, Orangutan manage to survive in these two areas and thus become endemic to them. One such conservation or rehabilitation centre is the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre (Fig. 13), in Sabah. In this centre young stranded baby Orangutans are looked after and later trained to survive and finally released into the natural forest. Confiscated Orangutans will also be trained and released. Besides Sepilok in Sabah, another rehabilitation centre is in Sarawak, the Semenggoh Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre. These two states of Malaysia are found in Borneo. Another rehabilitation centre is found in Sumatra, the Bohorok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre.[2][3] As for proboscis monkey, there had been no report on their existence in any other places in the world except for Borneo. Therefore we termed Orangutan as secondary endemics and proboscis monkey as primary endemics.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BIODIVERSITY

Dahiya 2006, [10] stated that living organism contributes to a wide variety of environmental services: regulation of gaseous composition of the atmosphere, protection of coastal zones, regulation of hydrological cycle and climate, generation and conservation of fertile soils, dispersal and breakdown of wastes, pollination of many crops, and absorption of pollutants.

Although values of biodiversity can be referred by many ideas, the values according to the present situation in Malaysia will be illustrated with example in Table 2. There are several authors that elaborate values of biodiversity (including Meffe & Carroll 1998 [11]) but closer to home, Mohd. Nordin Hj. Hassan 1991 [12] in his inaugural speech listed three values for biodiversity: direct values, optional values and intrinsic values. Direct values refer to the biodiversity being used directly for human needs. These biodiversity are food resources and building materials, used in genetic studies, in cultural rituals and in economic exchanges. Human can also gain benefit from biodiversity services. As an example, the root system of trees in the tropical rainforest ensures that ground water level is high, thus providing water to rivers and streams. Leaves of trees photosynthesise using carbon dioxide (exhaled by living organisms) and water to produce their own food. In that process, the waste product from the photosynthetic process is oxygen, which animals need for breathing, a critical life process for living things.

With regard to optional values, Mohd.Nordin Hj. Hassan 1991 [12] discussed the difficulty in placing future values for biodiversity available at present. Perhaps a practical example presently happening on the island of Borneo, is the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis; Fig. 14). During the 1950s this animal was abundant and commonly sighted in the Bornean rainforest. However, due to hunting for its horn, supposedly useful as an aphrodisiac, the number decreased drastically. Today, this animal is at the verge of extinction. So much money and effort are being put in to prevent its extinction – this animal has become very expensive. There are many other examples that indicated their increase in values as time goes by. Mohd. Nordin Hj. Hassan 1991, [12] discussed the intrinsic values where he elaborated that each and every single individual, species and ecosystem is unique. As such it is just right morally to allow for each one of them to strive and live and maintain itself.

Table 2: The values of biodiversity in Malaysia may be summarise as follows:

| Direct values | Indirect values | Optional values | Moral Values |

| Food: Rice, vegetables, spices, herbs (for flavour, colour) | Plants photosynthesis to produce oxygen for other organism | Nature -based tourism in Malaysia is an important industry. There is need to maintain quality of nature in Malaysia so that the industry remains sustainable(this encompasess flora , fauna and ecosystem). | The Rukun Negara dictates that Malaysian be believers. Religion in Malaysia like Islam and Christianity believe that men are created from the first human called Adam and Eve, in heaven. Human were then sent to the earth to believe in Him and care for what He has created and provided for, to be used by the future generations. Thus Malaysian appreciate life and respect life. |

| Building materials: Hard wood eg. teak (Tectona grandis, meranti (Shorea spp.) non timber forest products like rattan (e.g Calamus spp.) | Root system of tropical rainforest maintain high level of ground water feeding into river system useful for human consumption and industries. | ||

| Economic exchanges : Oil palm (Eleais guineensis), rubber (Hevea brazilliensis),cocoa (Theobroma cacao), pepper (piper nigrum) | Bees polinate to produce fruit and continue life cycle of plants | ||

| Medicines: Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia), misai kucing ( Orthisiphon Stamineus), Kacip fatimah (Labisia pumila), sea cucumber (Holothuria spp.) being used in product for healthcare | Fungi,bacteria, insects (e.g termites,ants and beetles) decompose dead plants and animal into nutrient to be recycled into the soil of tropical rainforest useful for trees to grow | ||

| Legumes enrich soil through their ability to turn nitrogen into nitrates needed by plant growth |

BIODIVERSITY OF MALAYSIA

The recent estimate shows that Malaysia is indeed a species-rich country. Table 3 (from several sources) showed that Malaysia has 3-30% of the global diversity. Malaysia has 3% of the global amphibian diversity and 30% of the marine fish diversity.

Table 3: Biodiversity (species richness and endemism) of Malaysia as compared to the world biodiversity.[4][5][13]

| TAXON | MALAYSIA/ENDEMIC | WORLD |

| Mammals | 286/27 (9%) | 4,630 (6%) |

| Birds | 736/11 (1.5%) | 9,950 (7.4%) |

| Reptiles | 268/69 (25%) | 7400 (3.6%) |

| Amphibians | 158/57 (36%) | 4,950 (3%) |

| Marine Fish | 158/57 (36%) | 13,321 (30%) |

| Freshwater Fish | 449/ N/A | 8,411 (5%) |

| Invertebrates | 150,000/ N/A | 1000,000 (15%) |

| Flowering Plants | 15,000/ N/A | 250,000 (6% |

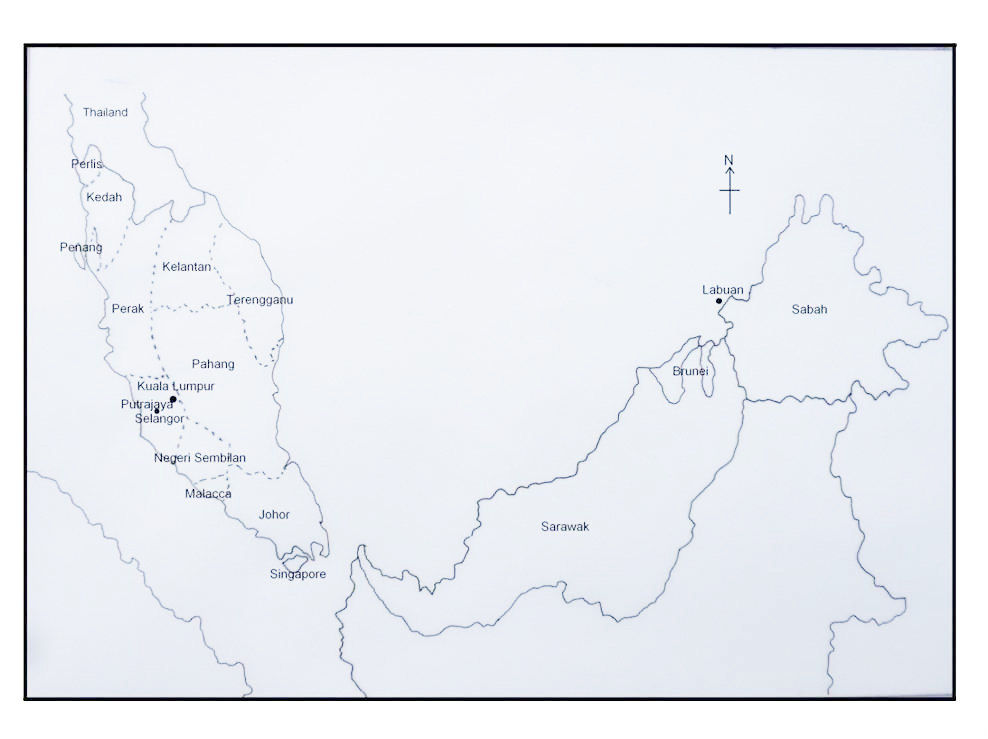

Malaysia is comprised of 13 states and three federal territories. Figure 15 shows the locations of the states and federal territories. Of the thirteen states, two – Sabah and Sarawak are on the island of Borneo. Borneo is the third largest island after Greenland and New Guinea. Even within the states of Malaysia, distribution of biodiversity varies. To illustrate the richness of biodiversity in Malaysia especially that from Borneo Table 4 gives the number of animal species found in some locations in Malaysia.

Table 4: Examples of biodiversity at several locations in Malaysia.

| No. of Species | Maliau Basin, Sabah [14] | Endau-Rompin, Selai, Johor [15] | Perlis State Park, Perlis[23][24] | GunungStong, Kelantan[40] | Crocker Range, Sabah[50] | Tabin, Sabah[58][59] |

| Size (km2) | 590 [14] | 870 [16] | >500 [25] | 21, 950 [41] | 139, 919 [51] | 120, 521 [60] |

| Trees | >440 [14] | N/A | 236 [26] ; 164 [27] | 406 [42] | 231 [52] | 225 [61] |

| Mammals | 86 [14] | 8 [17] (rodents) | 21 [43] | 14 [53] (non-flying) | 15 [62] | |

| Birds | 270 [14] | 206 [18] | 114 [30] ,24 [31] ,27 [32] | 57 [44] | N/A | 146 [63] |

| Reptiles | N/A | N/A | 46 [33] | 18 [45] | N/A | N/A |

| Amphibians | 46 [14] | 33 [19] | 13 [34] | 13 [46] | 50 [54] | 12 [64] |

| Freshwater Fish | 3 [14] | 76 [20] | 24 [35] , 17 [36] | 15 [47] | 41 [55] | 24 [65] |

| Insects | ||||||

| Butterflies | 33 [14] | 206 [21] | 25 [37] | 146 [48] | N/A | 310 [66] |

| Cicadas | N/A | N/A | 16 [38] ,16 [39] | 24 [49] | 20 [56] | N/A |

| Beetles | N/A | 269 [22] morpho sp | N/A | N/A | 273 [57] morpho sp | N/A |

Flora

It is estimated that Malaysia would have about 15,000 species of flowering plants. In the world, there are about 270,000 species. This means Malaysia has about 6% of the total global flora. In the plant kingdom there are the lower and higher plants. Lower plants are algae, mosses (Bryophytes – Fig. 16) and ferns and their allies (Pteridophytes) (Fig. 17).

Higher plants or Tracheophyta are flowering plants. They may be small (like grasses) or big and tall (like the legume tree of the tropical rainforest of Malaysia – the “tualang”, (Koompasia excelsa). They bear seeds, normally found within a fruit. Before fertilisation to become fruits, their ova (eggs – female fertile part) and pollen (male fertile part) are found on flowers. Their fruits such as pines (Pinus sp.) and conifers (Juniperus sp.) maybe naked (not found within fruit). Such group belongs to the Gymnospermae (Fig. 18). Another group of plant has seed embedded within a fruit. They are the Angiospermae. Among the angiosperms, there are plants producing seed with single food body (called cotyl). They are classified as Monocotyledonae. Examples are grasses, rice, palms and corn. More of the Angiospermae are dicotyl producing seeds with two food bodies. They are called Dicotyledonae. Examples are durian (Durio spp.) and all sorts of beans.

Although one of the most important timber trees of Malaysia is from the family Dipterocarpaceae, there are many non-timber forest plants that are of commercial values. An example is the rattan. Aminuddin 1994 [67] regarded rattan as most commercially important non-wood resource after timber in Malaysia. There is about 600 species of rattan in the world, 107 species are recorded from Peninsular Malaysia, and 20 are commercially used.[68]

Some plants in Malaysia are so unique as to become a tourism icons. This would mean that it has commercial values. An example is the Rafflesia, (Fig. 19), some species having the biggest flower in the world. It has no leaves and parasitic living only by attaching itself to a climbing woody vine or liana called Tetrastigma.

Fauna

The richness of plants is reflected also in the richness of animal diversity. As can be seen from Table 3. Malaysia has about 3-30% of the global animal diversity. The tropical rainforest of Malaysia has an estimated 150, 000 species of invertebrates mostly insects and this is about 15% of the total global fauna. The lowest is frog comprised of only 3% of global diversity (158 species of 4,950 species). However, considering the land-mass of Malaysia is only 0.2% compared to the global land mass, it is still big.

In Malaysia, information on animals focused greatly on large mammals. This is very true in terms of its conservation. One such effort is the newly created tiger conservation programme (Tiger Forever) supported by World Conservation Society in Johor National Parks. In Sabah, conservation of the Sumatran rhinoceros from an NGO, the Save Our Sumatran (SOS) Rhino and WWF has received much attention. Under the Darwin Initiative’s funding, the pygmy elephant is now being studied. Another iconic umbrella species is the orang-utan. Several international organizations are much concerned with the survival of these species. These include the Darwin Initiative Project (UK) and a locally based French NGO, the HUTAN which runs a program called Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Program (KOCP).[69]

Malaysia has 286 species of mammals which is higher than Sumatra with 201 species.[2] Among the 286, 27 are only found in Malaysia and nowhere else in the world. They are endemic to Malaysia (Table 3). This gives a value of 6% endemism. Among the 13 states, Sabah may have the highest number with 178 mammal species.[70] The biggest mammal group in terms of its diversity are the bats while the biggest mammal in size is the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) shown in Fig. 20.

In the marine environment, cetacean (marine mammals) sightings were found to be significantly higher in the East Malaysian South China Sea than the Sulu and Celebes Seas.[71]

Birds are an internationally popular group of animals receiving much tourism and scientific attention. More studies on birds are done in west Malaysia as compared to east Malaysia. It is stated that Malaysia has 736 species, comprising of 7.4% of the global diversity (9,950 species). An example of a unique bird in Malaysia is the hornbills, so called because of its huge bill. It is the icon bird for the state of Sarawak. As an example is the Pied hornbill (Anthrococeros coronatus) can be seen in Fig. 21 that has a beautiful white beak expanded to cover part of its head and this part is known as casque and marked with black. [74] Birds have received much attention for a long time as seen from old references such as wrote about the birds of Borneo.[72] Even till now, birds still draw attention from some writers, for example those writers that wrote about birds of Malaysia and Singapore.[72][73]

With the increasing global warming and warnings of areas drying, studies on amphibian are increasing. Both in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah and Sarawak scientists are increasing their effort to ensure that enough information is obtained so that any changes in the diversity pattern maybe related to the climatic changes. As such amphibian can be useful as indicator species. There are 158 species of amphibian in Malaysia. Of the three groups of amphibian, Malaysia has only two – the frog/toad and caecilians. Fig. 22 shows a toad species found in Malaysia.

Besides the amphibian, another group of interesting animal is the reptiles. Malaysia has 3.6% of the world’s reptiles. There are 268 species of reptiles of which 69 are endemic (25%). These include the snakes, lizards, turtles, tortoises, and crocodile. In Malaysia, there are some industries related to reptiles such as skin-product industry that uses skins of snakes and crocodiles. There is a venom centre in the state of Perak that extracts venom from various species of poisonous snakes for antidotes in cases of snake bites. There are seven turtle species in Malaysia, and one of them can be seen in Fig. 23.

Local communities in Malaysia consume some species of freshwater fish. They can be found in the rivers and streams as well as in the paddy fields during the wet season. Lakes located in Malaysia also provide freshwater fish, like the one in Fig. 24. Besides fish, there are other freshwater organisms such as freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium sp.), crabs, and shellfish. While for marine fish species despite having only 6.3% (712) of the global diversity (13,321), Malaysia consumed a small percentage of the species, including sharks and rays.

Since ancient times, the various ethnic groups in Malaysia have associated themselves with the different living components. For example, the Malay community will always have “sireh” (Piper betel) leaves during engagement and wedding ceremonies. The leaves will be decorated and is part of the man’s gift for his fiancé-to-be (Fig. 25). Besides its use in engagement and wedding ceremonies, “sireh” is also used by a village midwife to get rid of excessive wind in a newly born baby’s stomach. The leaves are warmed over a bowl of burning charcoals, and gently massaged onto the baby’s stomach, before the baby’s stomach is wrapped in a special cloth (barut). Another use of the sireh leaves is as an astringent. Some leaves are manually crushed in a bowl of water, and the water is used as a wash for lady’s private parts. And of course, old folks in Malaysian villages will chew the “sireh”. This is a tradition maintained by older folks of several ethnics, including Indian, Malay, and Dusun (of Sabah) for socialising.

However, as the nation develops, more natural resources are being used to bring more income for the country. More efficient methods are being used to harvest the resources, for example chainsaws to cut down forest trees, extensive damage occurs. This damages sometimes are more costly to repair, and at times are affecting human welfare. The Malaysian government is aware of the consequences of this phenomenon and through several efforts, at times jointly with non-governmental organisations, try to address the issues. As an example, the National Committee on Biodiversity had been established in 1994. In 2001 the National Biotechnology and Biodiversity Council was established, chaired by the Prime Minister of Malaysia.[75]

At the global level, Malaysian is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Malaysia signed and ratified the convention on 24th June 1994 and launched the National Policy on Biological Diversity on 16th April 1998. Prior to the formulation of policy, a country assessment of Malaysian biodiversity was carried out and a document “Assessment of Biological Diversity in Malaysia” was published in 1997. The ministry in charge of biodiversity preservation efforts, including the CBD is the Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment (MOSTE), which is currently called as Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE).[76]

CANOPY DIVERSITY

The tropical forest of Malaysia has huge trees that can reach to a height of 150-250 feet (50-80m). Since it is not easy to gain access and sample at that height, therefore, what occurs at this height remains a mystery. It is estimated that almost half of the global biodiversity may exist in the forest canopies, especially in the tropics and some techniques on how to get to the canopy are described.[77] In the Danum Valley, east Sabah during 1995, Project Hornbill was launched to try to do research on the canopy. An airship filled with helium gas (Fig. 26) was flown over the conservation area. It was a good initiative but the airship needed some more refinement. In 1996, some summarised methods have been used locally to gain access to the tropical rainforest canopy in Sabah: tree felling, tree climbing, tree tower, canopy walkways, cranes, fogging, helium filled solar powered airship (the Project Hornbill).[78] More recently, with funding from Darwin Initiative in collaboration with Universiti Malaysia Sabah, the Danum Valley and the Royal Society of UK, some students and staff of Universiti Malaysia Sabah and other government and NGOs within and from outside Malaysia were given training in Double Rope Climbing Technique to access the canopy, at Danum Valley. It is expected that more research findings from the canopy of Sabah rainforest will be published in the near future.[79]

INVASIVE SPECIES

Invasive species are species originating from some other parts of the world but brought in (mainly by man for trading or other reasons) to a new area and successfully colonise the native ecosystem. Major threats imposed by these invasive species include displacement of native species through predation, parasitism and so forth, alteration of habitats and/or disruption of native ecosystems processes.

In Malaysia, the classical example is the House crow (Corvus splendens – Fig. 27), brought to Malaysia to control the pests of coffee in the 1950s. After independence and when Malaysia no longer planted coffee on large scale, these crows were deprived of their food source. They then turned to scavenge other food sources. Today, this species is considered as pests as they are now in large population and is a nuisance when scavenging waste in rubbish bins.

Another classical example is the mile-a-minute plant (Mikania micrantha – Fig. 28). This species was not brought into Malaysia by humans deliberately. With their rapid growth and colonisation rate, this species moved southward from the neighbouring country and started to be a weed by smothering cover crops in oil palm plantation. Malaysia now spends large amounts of money to control this invasive species.

THREATS TO BIODIVERSITY IN MALAYSIA

The ultimate causes of biodiversity loss in Malaysia include human population growth together with unsustainable patterns of consumption, increasing production of waste and pollutant, urban development, international conflict and continuous inequities in the distribution of wealth and resources. In Malaysia, conversion of forested areas into other uses is one of the major causes of biodiversity loss. Another perhaps, is the unsustainable harvesting of resources such as fish bombing and logging. Similar to the world trend, water, soil and air pollution are also causing loss of biodiversity. Land degradation is also a cause for loss in biodiversity in Malaysia.[10]

Land conversions

Being a young and newly independent nation, Malaysia is moving fast into development. Despite, manufacturing being the top most income-generating sector, agriculture is still crucial to Malaysian economy. Today, Malaysia is the largest palm oil producer in the world. Extensive planting (Fig. 29) and good estate management are factors contributing to that. Rubber, cocoa and pepper still bring income to Malaysia although they are no longer the main cash crops in Malaysia. More recently the export list has grown longer to cover not only historically well-known crops such as pineapple but also banana, papaya, mangosteen, etc.

As more land has been converted to townships and for public amenities. To grow these crops on a large commercial scale, Malaysia needs agriculture land and thus forested land would be converted to agricultural land.

Malaysia has also long been the producer of excellent quality tropical hard wood. The typical group, the dipterocarps is said to originate from the island of Borneo. There are 291 species of dipterocarps recorded in Borneo.[80] The centre of evolution for dipterocarps is Borneo and distribution is within the narrow confine of the tropical belt, southern of Thailand, Indonesia, Borneo, Sumatra, and the Philippines. 75% of tropical hardwood in the global market is provided by Malaysian forests. This also encourages extensive logging activities. However, these activities have been much reduced since the peak in the 1980s.

Pollution

Large plantations in Malaysia tend to use organic fertiliser to produce higher yield. This has been named as one of the major cause of soil and water pollution. Excessive use of fertilisers causes chemicals to sink into the soil polluting the soil. In addition to prevent plant damage, large amount of pesticides and fungicides are used. To keep plantation free of weeds, herbicides are also used. All these agro-chemicals besides sinking into the soil, these chemicals may also leaves residues on plant parts or on top of soil. When there is a heavy rainfall, the raindrops wash away these chemicals and will again either sink into the soil or washed away on the surface into waterways, polluting the water.

One of the major problems with water pollution in Malaysia is the occurrence of agro-chemicals. If these polluted water is trapped into an area (as in lakes or pools), the high concentration of chemicals in the water, especially high-nitrate fertilisers, tend to cause eutrophication. This is phenomena when a water body becomes enriched with input of organic materials or surface run-off containing nitrates and phosphates which directly controls the growth of algae and other aquatic plants. [81] The rapid growth of algae and aquatic plants will cause the surface of the water to be covered. When these algae and plants die, it will cause a massive decomposition process and thus polluting the water body. Earthworks loosen soil and when these are carried into waterways will cause siltation and sedimentation (Fig. 30).

Another water pollutant is the large amount of wastes that are dumped into the river. These wasters are then brought to the sea. Some examples are plastic materials which are non-biodegradable. These materials, especially plastics bags will look like jelly fishes and thus the marine organisms such as turtles which love jelly fish will swallow them. This cause the turtles choked to death. These plastic bags could also be deposited on coral and suffocate them to death. In areas with poorer sanitation, people use rivers as toilets. Although no longer rampant, untreated human wastes bring problems, because of the high load of bacteria such as Escherichia coli.

One of the major causes of air pollution in Malaysia is the increasing numbers of vehicles on roads. It leads to high emission of noxious gases from the burning of fossil fuels. Other than that, smokes from factories too will add on to air pollution.

Marine Ecosystems

With the increase in human population growth, there is much demand for marine protein. Traditional fish catching is no longer sufficient to meet the demand. Secondly, fishing has always been considered as a traditional and menial job and as such many young people are turning to work in factories and clerical services. To meet demand of the rising population, sometimes people resort to using less environmental friendly harvesting methods. One example is the use of net with smaller mesh size as well as fish bombing and poisoning. These methods are indiscriminate and unsustainable as they kill marine organisms in large number, even the young ones and thus may reduce population substantially leading to extinction.

Pollution of the marine ecosystems comes about from oil spills, chemical and toxic wastes dumping. Heavy metals from factories and mines may eventually end up in the marine ecosystems via rivers and streams. Humans may also add on to the pollution problem. In heavily populated areas with inefficient sewage system, people tend to dispose of the bodily organic waste in aquatic ecosystems such as rivers and streams. These water systems are polluted with human waste and bacteria such as Escherichia coli.

In areas where there are heavy logging activities, the loose forest soil will be eroded by rainfall and brought into the streams, rivers and eventually to the sea. This heavy load of soil will cause silting at river mouth and lead to flooding as water spill over the river banks. The silts may also be brought out into the marine ecosystem. This cause silts to cover the corals, sea grasses and other sea lives. This will lead to destruction of the sea lives and eventually may lead to extinction. Silting and sedimentation from soil work can also cause by construction of infra-structure like houses, offices, schools and others.

It was reported that the destruction of coral reefs of Sabah affected by reduced water quality due to erosion, surface run-off and sedimentation. It also noted that land clearing in coastal areas and on islands for agriculture, development of new towns and villages cause direct and indirect destruction of coastal habitats such as mangroves and sea grasses which are natural filters, reducing sediment and nutrient from reaching the nearby coral reefs. Reefs in the Malaysian Spratly’s are likely to be affected by climatic change, such as high temperature events that can cause coral bleaching, reduce calcification, and changes to ocean and atmospheric circulations.[82]

Consumption of coral reef fishes

Malaysia has great diversity of marine fish. Table 3 above shows that of the 13,321 marine fishes species (WCMC), Malaysia has about 4,000 species making up 30% of the global fauna. However, the number of species consumed is not that many as in a list of 376 species (~10% of local species) of major food fishes, excluding sharks and rays.[83] These species of fishes could be found in the local wet market (Fig. 31). As more corals are being destroyed by various ways (like pollution, climate change, explosion, tourism), coral fish are also in danger. And if more coral fishes are consumed, the rate of extinction of these species may also be on the rise.

Wetlands

The notion that wetland are wasteland was also common among Malaysian. Wetlands are converted to fish and prawn ponds to increase aquaculture produce. Sometimes wetlands are converted through reclamation to increase land for buildings, new township, recreation and residential areas. Ecologically wetlands are important as water regulator and mitigation for flooding. In mangrove, the complex and dense root system provides for a safe breeding ground for many aquatic organisms. A large mangrove area will act as wave barrier and thus, prevent erosion of soil. In the year of 2004 tsunami event, coastal areas of Aceh, north of Sumatra, Indonesia was destroyed. Had there been mangrove along the seashore, the damage would have been much. Malaysia learned a lesson from that event and had put a stop to development of building and/or infrastructure in areas with mangroves.

More than 60% (over 2 million ha) of the world’s tropical peat land are found in South East Asian countries with the major proportions occurring in Indonesia and Malaysia.[84] Peatland forest adds to biodiversity. Some plants are adapted to living in waterlogged soil and not found elsewhere. Examples are Dryobalanops rappa, Shorea platycarpa, Dactylocladus stenostachys, and Gonystylus bancanus, which are dominant in the Klias peninsula peatswamps forests.[85][86] Peatswamp forest composition is much different from other forest types in Malaysia. There is not much peatswamp forest left in the world. The United Nation Development Programme (UNDP) granted Malaysia with some funds to look into conservation of peatswamp. Three areas had been chosen – Loagan Bunut in Sarawak, Klias in Sabah and South-east Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia.[84]

OVERCOMING THREATS TO BIODIVERSITY IN MALAYSIA

The timber producing tropical countries of the world, include Malaysia have been pressured to stop logging, in order to maintain the quality of environment for the global communities by preventing climate change. With scientific evidence-based data that provided through biodiversity research, the Malaysian government is now supporting conservation effort and encouraging every state to take into account the conservation matters.

Legislation

Biological Resources and Benefit Sharing Act 2017 (Act 795):

The most recent Act established to protect the potential development of Malaysia’s biological resources and to prevent biopiracy is the Access to Biological Resources and Benefit Sharing Act 2017 (Act 795). The Natural Resources and Environment Ministry declared the Act to be enacted in Malaysia in 2017 and the enforcement effective on 18 December 2022.

Malaysia enacted the Access to Biological Resources and Benefit Sharing 2017 Act (Act 795) in 2017 to enforce the Convention on Biological Diversity and any protocol to the Convention dealing with access to biological resources and traditional knowledge associated with biological resources, as well as the sharing of benefits arising from their use.

Under the Act, any local or foreign individual or corporation that intends to access Biological Resources or Traditional Knowledge associated with Biological Resources for commercial, potentially commercial or non-commercial purposes must obtain a permit; failure to obtain a permit may result in a penalty being imposed on the relevant party. Biological Resources covered in Act 795 include genetic, plant, organism, microorganism and traditional knowledge. [103]

According to Act 795, a person is said to have access to a biological resource if

the ‘access’ or ‘taking’ of a biological resource from its natural habitat or location where it is kept, grown, or discovered, including in the market, for the purpose of research and development;

Or

there is a reasonable prospect, as determined by the Competent Authority (CA), that a biological resource taken by the person will be subject to research and development. [104]

To refer to the mentioned Act:

Bahasa version

English version

Malaysian National Policy Biological Diversity:

Malaysian signed and ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1994. Assigning WWF to assess the status of biodiversity in Malaysia, the report was ready in 1997 (Fig. 32a). [13] Thereafter a policy was formulated (Fig. 32b). In the document, the vision and policy statements are made. There are 15 objectives to the policy and 15 strategies in implementing the policy. The vision of the CBD is to transform Malaysia into a world centre of excellence in conservation, research and utilisation of tropical biological diversity by the year 2020. While the policy statement is to conserve Malaysia’s biological diversity and to ensure that its components are utilised in a sustainable manner for the continued progress and socio-economic development of the nation.

Other policies:

Even before MNPB 1998, there are already other legislations in place.[13]

Peninsular Malaysia:

- Protection of Wildlife Act 1972

- National Forestry Act 1984

- Fisheries Act 1985

- National Parks Act 1980

- National Land Code 1965

- Land Conservation Act 1960

- Water Enactment 1920

- Land Acquisition Act 1960

- Local Government Act 1976

- Town and Country Planning Act 1976

- Environmental Quality Act 1974

- Plant Quarantine Act 1976

- Pesticides Acts 1974

- Exclusive Economic Zone Act 1984

- Petroleum Mining Act 1966 (revised 1972)

Sabah:

- Fauna Conservation Ordinance 1963

- Parks Enactment 1984

- Forest Enactment 1968

- Land Ordinance 1956

Sarawak:

- Wildlife Protection Ordinance 1990

- National Parks and Reserves Ordinance 1956

- Forests Ordinance 1954 (Chapter 126)

- Public Parks and Green Ordinance 1993

- Land Code 1957 (Chapter 81)

- Natural Resources and Environment Ordinance 1949 (Chapter 84)

At the international level Malaysia is a party to several conventions related to biodiversity conservation. Some are listed as below:

- Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna (CITES)

- RAMSAR Convention

- Bonn Convention

- Convention on Biological Diversity

Maintaining biodiversity of tropical rainforest

In the Malaysian constitution, natural resources including land and forest are state matters. Each state is now keen to conserve biodiversity available in their state. Several strategies were chosen, including establishment of protected areas.

Forest fire has been devastating to biodiversity. Most fires are started by people. Some states like Sabah have amended their legislation to implement higher penalty for people who started fires in forests. Illegal hunting is also a factor that could lead to loss of biodiversity. The state of Johor has made a drastic move by banning of hunting activities for all wildlife. Another legislative step taken up by the Malaysian government is that any timber logging activity involving 500ha or more of forested land will need an Environmental Impact Assessment.

Malaysia is currently one of the leading palm oil producers in the world. Both in Peninsular and Sabah/Sarawak, large tracts of land had been converted to accommodate for this crop. At this moment of time, the state of Sabah has the largest acreage of oil palm of about 1.3 million ha. This fast increase in development of oil palm plantation and fast conversion of land has cause concern to all.

Borneo is comprised of three nations: Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. It is known that each nation has its own conservation plan with the list of various activities. However in 2004, a meeting was organized in Brunei to discuss another approach to conservation. This new approach involves trans-frontier boundaries. This endeavour is called the Heart of Borneo. It would be a coordinated effort in conserving one of the highest biodiversity regions of the world.[87]

Maintaining marine biodiversity

Currently, Malaysia has 30% (~4,000 species) of the world’s marine fish fauna. It is a common knowledge that some unsustainable and indiscriminate harvesting methods such as fish bombing and poisoning are being practiced in Malaysian water. Therefore, it seemed logical to put a stop to such activities by several means. The best would be to educate people of the hazards and danger of such activities in terms of human safety and biodiversity conservation. Another way is through legislation.

Similar to the terrestrial ecosystem (the Heart of Borneo programme), the marine ecosystem management are also applying a large scale intervention to conserve marine biodiversity. One example is the newly introduced eco-region approach to conserve marine ecosystem of the Sulu-Sulawesi Eco-region programme initiated by WWF. An eco-region is defined as a relatively large unit of land or water that contains a distinct assemblage of natural communities, dynamics and environmental conditions. The core strategy to conserve the fullest possible range of biodiversity in an eco-region and the processes that maintain it is the establishment of a network of protection based on connectivity.[88]

The cooperation of armed forces (such as marine police and army) is necessary to ensure rules and regulations are being observed. International understanding is required when it comes to patrolling international waters.

Another pragmatic way of ensuring conservation of marine organisms is to provide for sufficient marine produce needed for the growing human population in the most efficient way. One such method is through cage farming of commercially important species of fish. This is being carried out in some parts of Malaysia.

To add on to this effort, Malaysian may want to increase intake of freshwater fish by making effort to popularise them. The production of freshwater fish could be increased through inland aquaculture using fish-ponds.

Maintaining wetland biodiversity

Wetlands had been considered as wasteland. There is strong demand that they be converted to fish-ponds or shrimp ponds to meet the need in aquaculture. In some Malaysian states like Sabah, some mangrove patches had been converted through the process of land reclamation to build infrastructures like offices, hotels and other recreational purposes. However, there is a twist to the story. With the recent events of tropical storms and tsunami that saw several countries like Indonesia, Thailand and Sri Lanka being destroyed because they do not have a wave protecting buffer such as mangrove, policy makers are now having favourable view in the protection of wetland, especially mangroves. Currently, Sabah has the biggest mangrove forest in Malaysia, covering 365,500ha or 57% of the country’s total and that for the last two decades, mangrove forests were chiefly managed for the production of firewood, poles, bark and charcoal. The current trend of management of mangrove forest in Sabah is still limited to the production of charcoal, firewood and poles for local consumption and thus insignificant in bringing in direct revenue to the state. Nevertheless, the functions of the mangrove ecosystem such as coast stabilization, erosion control, absorption of pollutants, biological filtering, as well as providing socio-economic benefits to local inhabitants are important for the state.[89]

In the Indonesian Borneo, Kalimantan, peat swamps have been drained to provide for agriculture. This mega project was a failure because the dried land will not support crops such as rice that need plenty of water. Consequently, people in Kalimantan are now trying to revive the peat ecosystems by blocking the drains.

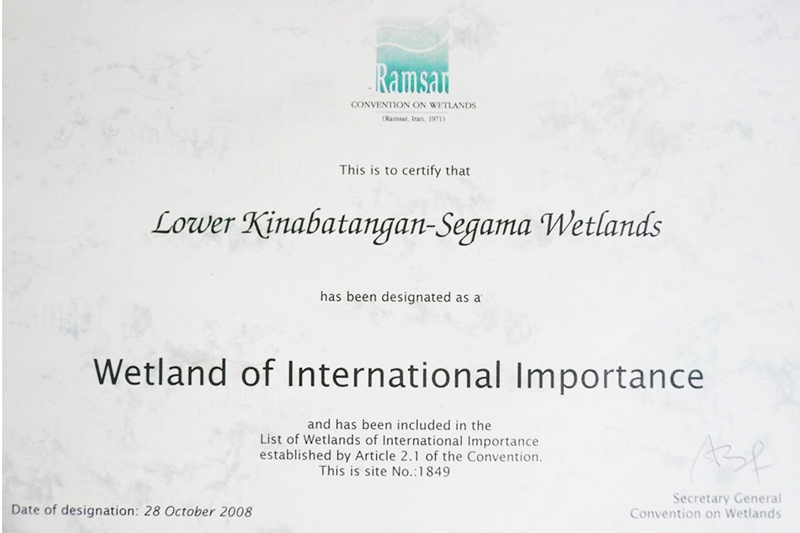

In Sabah, under the Bornean Biodiversity and Ecosystem Conservation (BBEC) programme, the sixth Ramsar site for Malaysia was established (Fig. 33). It is the largest and situated between two river catchments; the Kinabatangan and Segama.

Maintaining cultural biodiversity

There are more than 30 ethnic groups in Malaysia, especially in the two states on Borneo island. Each ethnic group has its own traditional knowledge. It happen to be a natural resource is used differently between ethnic groups and thus gives extra value of the resource. As Malaysia progresses on, people tend to be urbanized. Young people from villagers will migrate to towns and cities to look for better livelihood. Unfortunately, most of them will not practice traditional lifestyle in towns and cities. This traditional knowledge used by the older folks normally not being recorded. The knowledge will soon be forgotten.

Traditional knowledge is valuable. One example is the tagal system practised in Sabah. The Dusun of the Crocker Range and Kimanis who live along rivers will make an agreement not to harvest the fish for a certain period of time. When the season arrives, villagers only will harvest fish and only catching the big fish. After this, the next fish catching would need to wait for next season to come. This is indeed good for conservation.

Traditional ecological knowledge tends to erode among ethnic like the Dusun of Kimanis. For all reasons stated above, it is crucial that traditional knowledge be documented. Currently, some efforts have been made to document traditional knowledge.[90]

Public awareness and education

Conservation of biodiversity can be sustainable only when users of biodiversity are involved in the conservation. For this target, people have to be made aware of the importance of biodiversity and its conservation. In Malaysia, awareness for the conservation is much facilitated by the electronic media, the television and radio (especially to rural areas where the availability of television is restricted). Printed media like newspaper and magazines, which needs reading and comprehending capabilities are not that well used.

In general, a common Malaysian adult will not know much about biodiversity. They know about food, building materials and medicines as coming from plants and animals, but they do not understand how rich Malaysia is. This is a task that the government has to undertake as to educate Malaysian and increase their awareness on protecting the biodiversity. Appreciation will lead to a feeling of care and love. In fact, it could also be a tool to make Malaysian be patriotic of their natural resources.

In the school system of Malaysian, there is no separate subject on environment. As such, children do not understand its importance and values. However, all these issues have been highlighted to the Malaysian government. The government is trying out other strategies to overcome these problems.

A decision was made to establish a Natural History Museum (NHM) in Malaysia at the national level. The benefit besides providing education to all age groups will also include boosting:[91]

- tourism, because it will share the global reputation of natural history museums as a premier tourist attraction,

- higher education, because comprehensive collections in NHM Malaysia will enable Malaysian universities to offer world-class tropical biodiversity programmes, and

- economic development, because NHM Malaysia’s growing expertise on natural resources will be available to support the information needs of a growing economy

This effort will be much looked forward to by Malaysians. It will be an eye opener for Malaysians to realize the natural wealth that they have, and enlightening to learn of their uses. It is hoped that this will create a sense of patriotism and love towards the natural heritage. When this spirit has embedded in Malaysian, conservation is in practice.

ENHANCING THE VALUES OF BIODIVERSITY IN MALAYSIA

Discovering biodiversity (inventory)

Management could not be carried out effectively without knowledge of what is available in an ecosystem. An inventory is thus, critical and compulsory in order to prioritize actions to be taken. A full inventory may be quite difficult to perform, thus at times rapid assessment of biodiversity is needed. Throughout Malaysia, such effort is being carried out. As an example in Sabah, the Forestry Department has to document the biodiversity of Meliau Range, jointly with a private sector and an NGO.[91] Jointly with other stakeholders, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), a tertiary education federal institution based in Sabah, had documented biodiversity of various locations in Sabah.

Maliau Basin is an interesting location in Sabah due to its unique crater-like land formation. Its biodiversity was also being documented by a group of people after their second major expedition in Sabah.[92] An updated report for Maliau Basin has been done.[14] Tabin, a wildlife sanctuary on the eastern coast of Sabah was visited twice, the first visit was to the core protected area, and the second to the limestone area, and two reports had been published.[93] Biodiversity of the two remaining peat swamps forests of Klias in western Sabah was documented as well.[94]

In 2002, a trilateral cooperative effort between UMS, the state government and the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) called Bornean Biodiversity and Ecosystem Conservation (BBEC) programme was established.[95] As a prerequisite to formulation of management plan and to support conservation several expeditions were organized to various parts of Sabah. In 2002 also, an expedition was carried out to the Lower Kinabatangan, the famous floodplain of the longest river in Sabah and a report was published on its biodiversity.[96] The Crocker Range, the largest protected area in Sabah was documented as part of the programme.[97] A similar publication was done on the Lower Segama, where an ethnic group of Sabah, the Tidong lives.[98]

In Peninsular Malaysia, more recently, several expeditions had been carried out led by the National Parks and Wildlife Department (PERHILITAN) and the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM). This is part of activities planned under the National Biotechnology and Biodiversity Council. Earlier works though, had been reported from states such as Perlis [23][24]; Johor,[15] and Kelantan.[40]Several more publications reporting on biodiversity of other parts of Malaysia are expected to be available in the near future.

Carrying out inventory has its own set of problems. Inventory will normally need a lot of resources. To collect specimens, money has to be made available to go to the field and hire staff to do collection of specimens. Coordination has to be made to avoid duplicating efforts and ensure gaps are covered effectively.

Once collections are taken back to the laboratory, the specimens have to be processed and expertise is needed to curate the various groups of organisms. This is followed by identification that requires another set of expertise. Leading taxonomists for many biological groups are located far from Malaysia (Europe, America, Japan). In 1996, BioNET International initiated by CABI organization in the United Kingdom set up loops all over the world. This is to ensure that rich biodiversity countries of the south will be self-sufficient in taxonomist. BioNET International managed to convince the ASEAN Minister to set up a loop, now called ASEANET which is based in Serdang, Malaysia. It builds taxonomic capacity through four work programmes: establishment/improvement of information and communication services; training of taxonomists, applied scientists, technicians and para-taxonomists; rehabilitation of existing collections and records; development and use of computer aided and automated taxonomic tools.[99]

Discovering uses for biodiversity

Article 1 of CBD dictates that there should be equitable sharing of benefit derived from the use of genetic resources has not really materialized despite the many years of the CBD. Perhaps it is timely that the biodiversity rich nations began to explore on their own the uses of their biodiversity.[100]

In Malaysia, we have a long way to go in discovering uses for our biodiversity. Nevertheless, we have made a start by screening herbs that have well known uses among the indigenous people.[101]

In Malaysia, the use of herbs in healthcare had been practiced traditionally by the ancestors. In recent years, scientists have been trying to prove scientifically the mechanisms involved. Plants that have received much attention are kacip fatimah (Labisia pumila – Fig. 34), tongkat ali (Eurycoma longifolia – Fig. 35) and misai kucing (Orthosiphon stamineus – Fig. 36). Tongkat ali’s root and kacip fatimah’s are normally dried and cut to pieces before being boiled in water to be consumed as tea. For misai kucing, the leaves are dried and brewed like tea. Besides plant’s parts being dried, boiled and drunk like tea, some are eaten raw like salad. An example of a well known herb taken like salad is pegaga (Centella asiatica) and ulam raja (Cosmos caudatus). More plants are being screened for the purpose of detecting biologically important chemicals. Besides herbs, scientists are also looking into rare fruits such as native bambangan (Mangifera pajang) of Sabah.[102] Bambangan is from Anacardiaceae, the mango family.

Knowledge based industries

Another value of biodiversity is in the publishing industry. More books could be written, movies and documentaries made if more information is obtained about living things. The rich biodiversity areas in the tropics may be lacking trained scientists who are committed to produce such materials. Currently, more books are published about biodiversity in Malaysia as well as electronic media. For example, television is now showing more documentaries of biodiversity found in Malaysia.

Conservation ethics

In the Malaysian constitution, all Malaysian are supposed to be believers of one religion or another. The official religion of Malaysia is Islam. Other main religions and beliefs practiced in Malaysia include Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism. As such, the idea of protecting and maintaining life is not a problem since all these religions and beliefs practice it. Historically, Malaysian’s attitude towards the environment (including the living components) has been influenced by traditions and cultures. Respecting life is expected of all Malaysians. However, with the recent development and modernization, traditions and cultures tend to erode giving way to materialistic gain attitudes.

The government has charted the course of Malaysian development to be comparable and competitive with the global progress, i.e. the Malaysian Vision 2020, whereby, Malaysia hopes to achieve the status of a developed nation by that date. In doing so, one of the nine challenges outlined in the vision includes the need to balance development and conservation of the environment.

Awareness has to be created early to young Malaysians if they are to be assigned the agenda of sustainable development. Education has to be provided to all level of society of Malaysia to provide them with sufficient knowledge and skill to maintain the quality of life that we are enjoying now. These are tools to make Malaysian ethical about their environment. Another tool is naturally the legislation, which are available currently in Malaysia, and from time to time are revised to suit conditions and situations.

References

- Whitmore, T.C. 1998 An introduction to Tropical Rain Forest (2nd edition) Oxford University Press 282pp (p: 22,11)

- Whitten, T., Damanik, S.J., Jazanul Anwar & Nazaruddin Hisyam. 2000 The Ecology of Sumatra Vol. 1 Periplus Edition (HK) Ltd. (p:374, 36)

- Payne, J. and Prudente, C. 2008 Orang-utans : Behaviour, ecology and conservation New Holland Publisher (UK) Ltd. (p: 129)

- Gleich, M., Maxeiner, D., Miersch, M. & Nicolay, F. 2000 Cataloguing life on earth : Life Counts Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, 284pp

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre 1992 Global Biodiversity Chapman& Hall, London

- Mitchell, A.W. 1986 The enchanted canopy : Secrets from the rainforest roof Fontana/Collin 255pp (p: 22)

- Wilson, E.O. 1992 The diversity of life Penguin Books , England (p: zxii)

- Mitchell, A.W., Secoy, K. & Jackson, T. (eds) 2002 The Global Canopy Handbook : Technique of Access and Study in the Forest Roof Global Canopy Programme 248pp (p: 6) (p: 35; 4)

- Cox G.W. 1997 Conservation Biology second edition The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc, USA pp 362 (p: 35)

- Dahiya, M.P. 2006 Biodiversity Conservation Pragun Publications, India 272pp (p: 1)

- Meffe, G.K. and Carroll C.R. 1994 Principles of conservation biology Sinauer Associates, Inc Publishers, Sunderland, Massachusetts (p: 25)

- Mohd. NordinHasan. 1991 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pemuliharaannya Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 67pp

- MoSTE 1997 Assessment of Biological Diversity in Malaysia Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, Malaysia (p: 45)

- Hazebroek, H.P., Adlin, T.Z. & Sinun, W. 2004 Maliau Basin Sabah’s Lost World Natural History Publications (Borneo) 235pp (p: 4, 73, 115, 141, 144)

- Mohamed, H. Zakaria-Ismail, M. 2005 The forests and biodiversity of Selai Endau-Rompin Perbadanan Taman Negara Johor, Johor Bharu

- Davison, G.W.H. 1998 Endau Rompin : a Malaysian heritage Malayan Nature Society (p: 10)

- Mohd-Zain, S.N. and Syed-Arnez, A.S.K. 2006 Parasitofauna of the wild rat population oat Selai, Endau-Rompin National Park, Johor, Malaysia In : Mohamed, H. & Zakaria-Ismail, M. 2005 The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp 215-218 (p:215)

- Ramli, P., Daicus, B. and Hashim, R. 2006 A preliminary checklist of birds at Lubuk Tapah, Endau-Rompin National Parks, Johor, Malaysia In: Mohamed, H. & Zakaria-Ismail, M. 2005 The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp 205-210 (p:205)

- Daicus, B. and Hashim, R. 2006 Amphibian of the Lubuk Tapah and adjacent areas in southwestern Endau-Rompin National Parks, Johor, Malaysia In : Mohamed, H. &Zakaria-Ismail, M. (eds) The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp:199-204 (p:199)

- Zakaria-Ismail and Fatimah, A. 2006 The fish fauna of the Hulu Selai river system, Endau-Rompin National park, Johor, Malaysia In : Mohamed, H. & Zakaria-Ismail, M.(eds) The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp 191-198 (p:191)

- Sofian-Azirun, M., Khaironizam, M.Z., Norma-Rashid, Y. and Daicus, B. 2006 Butterflies (insects : Lepidoptera) of the southwestern Endau-Rompin National Park, Johor, Malaysia In : Mohamed, H. & Zakaria-Ismail, M.(eds) The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp 169-188 (p: 169)

- Fauziah, A. 2006 Diversity and abundance of beetles in the lowland forest of southwestern Endau-Rompin National Park, Johor, Malaysia In : Mohamed, H. & Zakaria-Ismail, M.(eds) The Forests and Biodiversity of Selai Endau Rompin, University of Malaya pp 153-157 (p:153)

- Latif, M., Kassim, O., Yusoff, A.R. & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negeri Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosial Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Perlis pp. 407

- Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman, Latiff, A. 2002 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negeri Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian Jabatan Perhutanan Perlis.

- Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (p: 26)

- Latiff, A.M., Faridah-Hanum, I., Zainuddin Ibrahim, A. Shamsul Kamis, Nazre, M and Mat-Salleh, K. 2002 An annonated checklist of plants of Wang Mu forest reserve, Perlis State Park In : Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (259-289) (p: 281)

- Faridah-Hanum, I., Mat-Salleh, K, Rahim Othman, A., Rizal Khalit, A, Shamsul Kamis, Nazre, M., Zainudin Ibrhaim, A. and Latiff, A.M. 2001 An annotated checklist of flowering plants at Wang Kelian, Perlis Sate Park, Perlis In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp: 227-247) (p: 227)

- Shukor, Md.N., Shahrul A.M.S., Raymond, W., Yusoff Ahmad, Ganesan Muthaiya and A.K. Jalaludin Pg. Besar 2002 Ekologi dan kepelbagaian mamalia kecil dan kelawar di hutan simpan Wang Burma, Taman Negeri Perlis In : Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (207-231) (p: 207)

- Shukor Md. Nor, Shahrul Anuar Mohd. Sah, Mohd. Hifni Baharuddin, Yusoff Ahmad, Ganesan, M. and Mohd. Zulfikar Kamili. 2001 Tinjauan mamalia kecil di Tasik Meranti, Taman Negara Perlis In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp: 181-192) (p: 181)

- Noramly, G. & Kanda Kumar 2001 A report of the bird survey at Perlis State Park especially at Wang Burma In : Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (191-208) (p: 191)

- Shahrul Anuar M.S., Shukor Md. Nor, Raymond, W., Yusoff Ahmad, Ganesan Mutahiya & A.K. Jalaludin Pg. Besar 2001 Tinjauan burung di hutan Sumpan Wang Burma dan Wang Mu, Taman Negeri Perlis (Bird survey in Wang Burma and Wang Mu Forest Reserves, Perlis State Park) In : Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (173-189) (p: 173)

- Shahrul Anuar Mohd. Sah, Shukor Md. Nor, Mohd. Hifni Baharuddin, Yusoff Ahmad, Ganesan, M. and Mohd. Xulfikar Kamili 2001 Tinjauan burung di Tasik Meranti, Wang Kelian, Taman Negara Perlis In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp:167-179) (p: 167)

- Sharma, D.S., Shahrul Anuar Mohd. Sah, Sharma, R.S.K. and De Cruz, R.M 201 The reptilian fauna of Perlis State Park at Mata Ayer and Bukit Wang Mu Forest Reserves In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp: 129-137) (p: 129)

- Ibrahim Jaafar, Mohd. Ali Ektella and Sharul Anuar Md. Sah 2001 The diversity of amphibians at Taman Negeri Wang Kelian In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp: 123-127) (p: 123)

- Abdullah Samat, Amirudin Ahmad, Gires Usup & Maimon Abdullah. 2001 Fishes of Perlis State Park In : Latiff, A.M., Kasim Osman, Yusoff A. Rahman & Faridah-Hanum, I. 2002 Perlis Biodiversity and Management of Perlis State Park : Physical, Biological and Social Environment of Wang Mu Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri (pp: 135-147) (p:138)

- Amiruddin, B.A., Ahyaudin B. A. and Mashor Mansor 2001 Freshwater fishes of Wang Kelian, Perlis Satet Park In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp: 111-121)

- Zaidi, M.I., Azman, S. and Ismail, S. 2001 Butterfly (Lepidoptera : Rhopalocera) fauna of Wang Kelian, Perlis Satet Park In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp:161-165)

- Zaidi, M.I., Azman, S., Noramly, B.M. & Ruslan, M.Y. Cicada (Homoptera : Cicadoidea) fauna of Perlis State Park : Additional survey results and overview In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp:157-164) (p: 157)

- Zaidi, M.I., Azman, S. and Ruslan, M.Y. Cicada (Homoptera : Cicadoidea) fauna of Wang Kelian Park, Perlis In : Faridah-Hanum, I., Kasim Osman and Latiff, A.M. 2001 Kepelbagaian Biologi dan Pengurusan Taman Negara Perlis : Persekitaran Fizikal dan Biologi Wang Kelian (pp:149-160) (p: 149)

- Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia

- Nik Abdul Azizi Nik Mat 2005 Perutusan Menteri Besar Kelantan In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (p: 8)

- Chee, B.J., Lim, C.K., Kamarudin, S., Markandan, M., Shamsul, K., Manap, T.A., Lim, K.H., Ku Yahya K.H., Abdul Razak, A. & Latiff, A. 2005 A preliminary checklist of plants species of the Gunung Stong Forest Reserve In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (eds) Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 319-340) (p: 319)

- Shukor, M.N., Shahrul Anuar, M.S., Nurul Ain, E., Norzalipah, M., Norhayati, A., Nadzri, A., Yusoff Ahmaed, Mohd. Yusof, O., Ganesan, M. & Kalimuthu, S. 2005. Tinjauan mamalia kecil di Hutan Simpan Gunung Stong In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 227-236) (p: 227)

- Shahrul Anuar, M.S., Shukor, M.N., Norzalipah, M., Nurul Ain, E., Yusoff Ahmad, Rahim, A., Puan, C.L., Mohd. Yusof, O., Nazri, A. & Kalimuthu, S. 2005. Bird survey of Gunung Stong Permanent Forest Reserve In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 215-226) (p: 215)

- Sharma, D.S.K., Ahmad Zafir Abdul Wahab, Surin Sussuwan, Norhayati, A., Mark Rayan Darmaraj & Oriane Ansel 2005 A note on the reptiles observed at Gunung Stong Forest Reserve, Gunung Basor Forest Reserve and around Jeli, Kelantan In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp:199-205) (p: 199)

- Norhayati, A., Zaiton, S., Julianan, S. & Shukor, M.N. 2005 Kepelbagaian dan kelimpahan amfibia di Hutan Simpan Gunung Stong, Kelantan In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 180-190) (p: 180)

- Abdullah Samat, Shukor, M.N., Mohd. Yusoff Ahmad & Mazlan, A.G. 2005 Fishes of torrential unnamed tributaries of Sungai Galas in Gunung Stong area In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 206-214) (p: 206)

- Zaidi, M.I., Azman, S., Norela, S. & Poh, L.S. 2005 Butterfly (Lepidoptera : Rhopalocera) fauna of Gunung Stong Forest Reserve In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 168-179) (p: 168)

- Azman, s. & Zaidi, M.I. 2005 Cicada (Homoptera: Cicadoidea) fauna of Gunung Stong Forest reserve In : Shaharuddin Mohamad Ismail, Dahalan Hj. Taha, Abdullah Sani Shafie, Jalil Md. Som, Faridah-Hanum, I. & Latiff, A. (pnyt) 2005 Taman Negeri Gunung Stong, Kelantan : Pengurusan, Persekitaran Fizikal, Biologi dan Sosio-ekonomi Jabatan Perhutanan Semenanjung Malaysia (pp: 130-145) (p: 130)

- Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. 2004 Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp268

- Kusano, T. 2004 Conservation of Crocker Range Park In : Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. & Nais, J. 2004 Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: ix

- Repin, R., Sumbin, D., Parmin, R., Johalin, Y. & Johalin, G. 2004 Additions to the checklist of the plants of Crocker Range Park In : Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. (eds) Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 39-50 (p:39)

- Bernard, H., Kalsum Mohd. Yusah, Yasuma, S. & Lucy Kimsiu. 2004 A survey of the non-volant mammls at several elevations in and around Crocker Range Park In : Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. (eds) Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 113-130 (p: 113)

- Kueh, B.H., Ahmad Sudin, Matsui, M. & Maryati Mohamed. 2004 Notes on the anuran of Crocker Range Park In: Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. (eds) Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 103-112 (p: 112)

- Mohd. Fairus Jalil, Ariffin Awang Ali, Mohd. Nadzri Ishak, Lucy Kimsui & Maryati Mohamed. 2004 Updates and revisional notes on the freshwater fishes of Crocker Range Park In: Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. (eds) Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 99-102 (p: 99)

- Zaidi, M.I., Azman, S., Ruslan, Mohd. Y. & Nordin Wahid. 2004 Cicada (Homoptera: Cicadoidea) fauna of Crocker Range Park : Further survey and overview In : Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. & Nais, J. (eds) Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 187-202 (p: 187)

- Chung, Y.C., Ansis, R.L., Allai, M., Saman, M. & Sikodoh N. 2004 Beetle (Coleoptera) specimens along Ulu Kimanis- Keningau road, Crocker Range Park In : Maryati M., Zulhazman, H. Tachi, T. &Nais, J. 2004 Crocker Range Scientific Expedition 2002 Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 203-210 (p: 203)

- Maryati Mohamed, Andau, M., Mohd. Noh Dalimin & Titol, P.M. 1999 Tabin Scientific Expedition Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 168

- Maryati Mohamed, Schilthuizen&Andau, M. 2003aTabin Limestone Scientific Expedition 2000 Universiti Malaysia Sabah 180pp

- Maryati Mohamed 1999 Executive summary In : Maryati Mohamed, Andau, M., Mohd. Noh Dalimin & Titol, P.M. 1999 Tabin Scientific Expedition Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 1-6

- Fujii, T., Takahashi, A., Ishida, H., Magintan, D. & Maryati Mohamed. 1999 Preliminary list of seed plants in Tabin Wildlife Reserve In :Maryati Mohamed, Andau, M., Mohd. Noh Dalimin & Titol, P.M. (eds) Tabin Scientific Expedition Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 49-60 (p: 49)

- Bernard, H., Lucy Kimui, Jumrafiah Abd. Shukor & Mohd. Soffian Abu Bakar. 1999 A Checklist of The Non-Volant Small Mammals in Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Sabah In:Maryati Mohamed, Andau, M., Mohd. Noh Dalimin & Titol, P.M. (eds) Tabin Scientific Expedition Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 145-152 (p: 145)

- Jomitin, C. 1999 Notes on the birds and mammals of Wildlife Reserve In: Maryati Mohamed, Andau, M., Mohd. Noh Dalimin & Titol, P.M. (eds) Tabin Scientific Expedition Universiti Malaysia Sabah pp: 153-164 (list on p: 160-163)