Scientific Name

Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd

Synonyms

Acacia acicularis Willd., Acacia densiflora (Small) Cory, Acacia ferox M.Martens & Galeotti, Acacia indica (Poir.) Desv., Acacia lenticellata F.Muell., Acacia minuta (M.E.Jones) R.M.Beauch., Acacia pedunculata Willd., Acacia smallii Isely, Farnesia odora Gasp., Farnesiana odora Gasp., Mimosa acicularis Poir., Mimosa farnesiana L., Mimosa indica Poir, Mimosa suaveolens Salisb., Pithecellobium acuminatum M.E.Jones, Pithecellobium minutum M.E.Jones, Poponax farnesiana (L.) Raf., Vachellia densiflora Small, Vachelia farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn. [1]

Vernacular Name

| Malaysia | Bunga Siam, laksana, pokok laksana, pokok lasana [2] |

| English | Cassie, cassie flower, cassy, dead finish, Ellington curse, Farnese wattle, fragrant acacia, huisache, mimosa, mimosa bush, mimosa wattle, needle bush, north-west curare, prickly mimosa bush, prickly moses, scented wattle, sheep’s briar, sponge tree, sponge wattle, sweet acacia, sweet wattle, thorny acacia, thorny feather-wattle, wild briar [2] |

| China | Ya zo shu pi [2] |

| India | Ari velam, arimaedah, arimeda, babbula, babul, barangay daru, devbabhul, gandharii, gandhelo babul, girimeda, hirjua-araung, irimeda, jait, kadam kapoor, kapur, kasturi tuma, marudruma, nang nuk kyeng, rimeda, tarua kadam, vetumul, vetuvali, vilaiti babul, wilayati kikar [2] |

| Indonesia | Bunga bandara, bunga mestu, bunga metu, kembang jepun, sari konta [2] |

| Thailand | Khamtai, krathin-hom, krathin-thet [2] |

| Laos | Kan ‘thin ‘na:m, kho:n ko:ng dê:ng, kho:n ko:ng ‘na:m [2] |

| Myanmar | Nan-lon-kyaing [2] |

| Philippines | Aroma, kamban, kambang, kandaroma [2] |

| Cambodia | Sâmbu:ë mi:ëhs [2] |

| Vietnam | C[aa]y keo ta, keo (the same name also for Murraya paniculata and Leucaena leucocephala), keo ta, keo th[ow]m, keo thi[ees]u, kou kong, kraul, kum tai, man coi [2] |

| Japan | Kin-gôkan (= golden Albizia lebbeck)[2] |

| Madagascar | Dintringahy, hatika, ramiarimbony, roycassy, roy-vazaha [2] |

| Nigeria | Boni, ewo-bomi, opoponax [2] |

| Argentina | Aranas, aroma, bonni, cachito de aromo, cassie, churqui, espinillo, espino blanco, esponja, espojeira, kuntich, subin, tusca [2]. |

Geographical Distributions

Acacia farnesiana originated in the northern part of tropical America, where its closest relatives can also be found. It is the most widely distributed Acacia species, introduced to all tropical and subtropical regions of the world for its fragrant flowers and has become widely naturalized and sometimes weedy, e.g. in the southern United States and Australia. In Malesia, the Spaniards first introduced it to the Philippines from Mexico. It is now recorded throughout South-East Asia. It was first cultivated in Europe in the Hortus Farnesianus in Italy in 1611 and has become an important crop in Southern France. [3]

Botanical Description

A. farnesiana is a member of the Leguminosae family. It is a branched shrub or rarely a small tree up to 4(-10) m tall. The bark is rough and light brown. The branchlets are cylindrical, greyish-brown to purplish-grey, hairless with prominent lenticels. [3]

The leaves, lateral shoots and peduncles are arranged alternate, often arising from short spurs on older wood. The leaflet is arranged in pairs along each side of a common axis twice and compound. The whitish-grey stipules are sharp-pointed, straight, up to 5 cm long. The petiole is 0.5-1.3 cm long, with a circular, sessile and often raised gland present in the distal half. It has a 4-6 cm long rachis, sometimes with a gland near the apical leaflet of a pinnate leaf. The base is truncate while the apex is asymmetrically acute, ending abruptly in a short stiff point. Both surfaces are hairless with the main vein is not centred, lateral veins beneath are raised and prominent. [3]

The inflorescence is composed of spherical stalk with a cluster of heads in a common ring of 50-60 flowers, aggregated in groups of 1-7 flowers in the upper leaf-axils. The stalk is 0.8-3.5 cm long, with a ring of bracts (involucel) at the summit and hidden by the flowers. The flowers are sessile, with 5 parts in a flower-whorl, golden-yellow and fragrant. The sepal is 1-1.3 mm in diametre, tube hairless with five 0.2 mm long teeth, triangular, acute, hairless except for the exterior of the apex. The petal is 2.3-2.5 mm long and the tube is hairless. The lobes come in 5, elliptical and about 0.5 mm long. It is acute, scarcely covered with short soft hairs at the apex. The stamens are numerous, 4-5.5 mm long with glandless anthers. The ovary is supported by a small 1.5 mm long stalk, densely covered with short soft hairs. [3]

The fruit is mostly slightly curved (sometimes straight), cylindrical pod, 4-7.5 cm x 1-2 cm, turgid, dark brown to black, rigidly papery, hairless and indehiscent. Veins are obliquely longitudinal, with some cross connection of reticulate veins. [3]

The seeds are ellipsoidal, 7-8 mm x 4-5.5 mm, in 2 rows, obliquely transverse in the pod, embedded in a sweet pulp. They are slightly flattened, olive-brown to olive-green also light brown to dark brown or black. The areole is elliptical, 6.5-7 mm x 4 mm, opens towards the scar on the seed that indicates its point of attachment. [3]

Cultivation

A. farnesiana is mostly found as a dominant component of secondary vegetation in dry places, but tolerates a wide range of annual rainfall (up to 4000 mm) and prefers a long dry season. Annual rainfall in its habitat in Australia ranges from 150-700 mm. It requires a mean annual temperature of 15-28°C and occurs from sea level up to 1500 m altitude. Its natural distribution in Malesia is up to 400 m altitude, while in cultivation it grows up to 1200 m. Frost is tolerated to a minimum of -5°C. It is found scattered or in pure, open stands in plains, savanna grasslands, tidal flats, sandy river beds, brushwood, and waste ground, on heavy soils including black clays, loamy or sandy soils with a pH of 5-8(-10). In France, however, A. farnesiana may grow and flower poorly on alkaline soils. It tolerates saline conditions and fire. [3]

Chemical Constituent

Essential oil of A. farnesiana has been reported to contain mainly methyl salicylate, anisaldehyde, geraniol, nonadecane, benzaldehyde, geranial [4], and various minor compounds [5][6][7][8]. Various non-volatile terpenes were also isolated from A. farnesiana seeds such as diterpene glycoside (e.g. farnesiaside). [9]

The mucilage from the pods A. farnesiana has been reported to contain polysaccharides (e.g. arabinose, xylose, galactose, glucose, and mannose) [10]. The pods also contain phenolics (e.g. gallic acid and a few derivatives such as ellagic acid, m-digallic acid, methyl gallate), flavonoids (e.g. kaempferol, aromadendrin, diosmetin and naringenin), their glycosides and galloylglycosides. [11][12][13][14]

The A. farnesiana seeds have been reported to contain flavone diosmetin, sitosterol glucoside, and flavone farnisin (e.g. 7,3′-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone). [13]

The A. farnesiana leaves have been reported to contain various flavonoids (e.g. apigenin-6,8-bis(C-β-D-glucopyranoside)) [15]. The leaves, pods and bark of the tree also contain significant quantities of tannins [16].

A. farnesiana pods have been reported to contain a sulphur-containing amino acid (e.g. N-acetyl-l-djenkolic acid) [17] which accounts for the quite high production of carbon disulfide by the roots of this plant [18].

A. farnesiana dried foliage have been reported to contain cyanogens (e.g. linamarin and lotaustralin). [19][20]

Plant Part Used

Bark, fruits, flower. [21]

Traditional Use

People in Mexico and Central America has been traditionally consumed infusion of the A. farnesiana bark or flower as an antidiarrhoeal, antispasmodic and astringent, as well as againsts dyspepsia. The fruit is used to strengthen teeth and to relieve cold sores. [21]

Preclinical Data

Pharmacology

Antimicrobial and antiparasitic activity

Tannin-rich extracts of leaves of A. farnesiana showed a significant but delayed bactericidal activity on Clostridium perfringens, but not on Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. When used in presence of germs cultivated on rumen fluid-agar medium, which contains rumen bacteria, protozoa and plant proteins, the activity of the extract is much reduced. [22]

During the screening of 32 Mexican medicinal plants for their activity on Vibrio cholerae, extracts of A. farnesiana were shown to inhibit the growth, the enterotoxin production as well as the adhesion of the bacteria [23]. Researchers showed that ethanolic extracts of most parts of Egyptian sweet acacia could inhibit gram positive bacteria, the leaf extract could also inhibit gram negative bacteria, while most of the extracts had no effect on pathogenic fungi [24]. However, a leaf extract of Indian sweet acacia could inhibit fruit rotting fungi and was able to prolong the shelf life of mandarin oranges for 10 days [25]. A bark ethanolic extract from a Colombian specimen showed good in vitro activity on Plasmodium falciparum (IC50 = 1.3 mg/mL), while the leaf extract was inactive. However none of these extracts was active in vivo [26]. All the above is consistent with the presence of high levels of tannins in the bark of this plant.

Anti-inflammatory activity

When administrated at the relatively high dose of 400 mg/kg i.p. to rats, methanol extracts of A. farnesiana were able to reduce carrageenan-induced paw oedema comparably or better than phenylbutazone (20 mg/kg) and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (12 mg/kg) [27]. The flavonoids apigenin-6,8-di-C-b-d-glucopyranoside (vicenin-2) and linamarin which have been isolated from the leaves were reported for its antioxidant and antioedematous properties which could account for the described effect [15][28].

Hypoglycaemic activity

Study reported a marked hypoglycaemic activity for the ethanolic extract obtained from the various parts of the sweet acacia. [24]

Toxicity

An extensive report on the toxicity of various products used in cosmetics and obtained from several Acacia species, including A. farnesiana concluded that, except for A. senegal, there was a lack of evidence to allow for any conclusion to be reached. [29]

Clinical Data

No documentation

Poisonous Management

No documentation

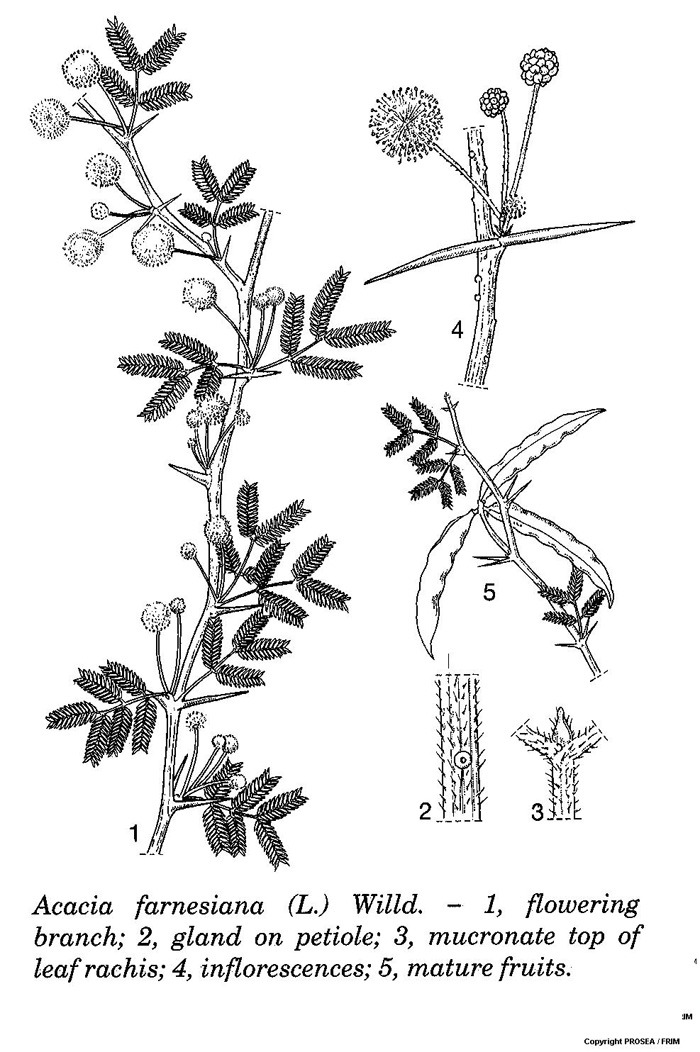

Line Drawing

References

- The Plant List. Ver1.1. Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. [homepage on the Internet]. c2013 [updated 2010 Jul 14; cited 2016 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/ild-423

- Quattrocchi U. CRC world dictionary of medicinal and poisonous plants: Common names, scientific names, eponyms, synonyms, and etymology. Volume I A-B. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2012. p. 19.

- Uji T, Toruan-Purba AV. Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. In: Oyen LPA, Nguyen Xuan Dung, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 19: Essential-oil plants. Leiden, Netherlands: Backhuys Publisher, 1999; p. 53-57.

- Flath RA, Mon TR, Lorenz GC, Whitten J, Mackley JW. Volatile components of Acacia sp. blossoms. J Agric Food Chem. 1983;31(6):1167–1170.

- La Face D. Contributo alla conoscenza dell’essenza concreta di gaggia farnese (Acacia farnesiana Willd.). Helv Chim Acta. 1950;33(2):249-256. Italian.

- Demole E, Enggist P, Stoll M. Odorous absolute oils of cassie (Acacia farnesiana). Helv Chim Acta. 1969;52:24-32.

- El-Hamidi A, Sidrak I. The investigation of Acacia farnesiana essential oil. Planta Med. 1970;18(1):98-100.

- Ehret C, Maupetit P, Petrzilka M. New components from cassie absolute (Acacia farnesiana Willd.). Rivista Italiana EPPOS. 1991:348-364 (No Spec, J Int Huiles Essent. 9th, 1990).

- Sahu NP, Koike K, Banerjee S, Achari B, Jia Z, Nikaido T. A novel diterpene glycoside from the seeds of Acacia farnesiana. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(48):8405-8408.

- Abd El-Wahab SM, Wassel GM, Aboutabl EA, Ammar NM, Afifi MS. Investigation of mucilage of the pods of Acacia nilotica L. Willd and Acacia farnesiana L. Willd growing in Egypt. Egypt J Pharm Sci. 1992;33:319-325.

- El Sissi HI, El Ansari MA, El Negoumy SI. Phenolics of Acacia farnesiana. Phytochemistry. 1973;12(9):2303.

- El Sissi HI, Saleh NAM, El Negoumy SI, Wagner H, Iyengar MA, Seligmann O. Prunin-O-6”-gallate from Acacia farnesiana. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:2843-2844.

- Sahu NP, Achari B, Banerjee S. 7,3′-Dihydroxy-4′-Methoxyflavone from seeds of Acacia farnesiana. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(5):1425-1426.

- Barakat HH, Souleman AM, Hussein SAM, Ibrahiem OA, Nawwar MAM. Flavonoid galloyl glucosides from the pods of Acacia farnesiana. Phytochemistry. 1999;51:139-142.

- Thieme H, Khogali A. Isolation of apigenin-6,8-bis(C-b-D-glucopyranoside) from leaves of Acacia farnesiana. Pharmazie. 1974;29:352.

- Rama Devi S, Prasad MNV. Tannins and related polyphenols from ten common Acacia species of India. Biores Technol. 1991;36(2):189-192.

- Gmelin R, Kjaer A, Olesen Larsen P. N-acetyl-L-djenkolic acid, a novel amino acid isolated from Acacia farnesiana Willd. Phytochemistry. 1962;1(4):233-236.

- Piluk J, Hartel PG, Haines BL, Giannasi DE. Association of carbon disulfide with plants in the family Fabaceae. J Chem Ecol. 2001;27(7):1525-1534.

- Seigler DS, Conn EE, Dunn JE, Janzen DH. Cyanogenesis in Acacia farnesiana. Phytochemistry. 1979;18(8):1389-1390.

- Janzen DH, Doerner ST, Conn EE. Seasonal constancy of intra-population variation of HCN content of costa rican Acacia farnesiana foliage. Phytochemistry. 1980;19(9):2022-2023.

- Garcia-Alvarado JS. Traditional uses and scientific knowledge of medicinal plants from Mexico and Central America. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2001;8(2-3):37-90.

- Sotohy SA, Mueller W, Ismail AMA. In vitro effect of Egyptian tannin-containing plants and their extracts on the survival of pathogenic bacteria. Deutsche Tieraerztliche Wochenschrift. 1995;102(9):344-348.

- García S, Alarcón G, Rodríguez C, Heredia N. Extracts of Acacia farnesiana and Artemisia ludoviciana inhibit growth, enterotoxin production and adhesion of Vibrio cholerae. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;22(7):669-674.

- Wassel GM, Abd El-Wahab SM, Aboutabl EA, Ammar NM, Afifi MS. Phytochemical examination and biological studies of Acacia nilotica L. Willd and Acacia farnesiana L. Willd growing in Egypt. Egypt J Pharm Sci. 1992;33(1-2):327-340.

- Tripathi P, Tripathi P, Dubey N K. Evaluation of some plant extracts in the management of blue mould rot of mandarin oranges. Indian Phytopathol. 2003;56:481-483.

- Garavito G, Rincón J, Arteaga L, et al. Antimalarial activity of some Colombian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107(3):460-462.

- Meckes M, David-Rivera AD, Nava-Aguilar V, Jimenez A. Activity of some Mexican medicinal plant extracts on carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(5):446-451.

- Martínez-Vázquez M, Ramírez Apan TO, Lastra AL, Bye R. A comparative study of the analgesic and antiinflammatory activities of pectolinarin isolated from Cirsum subcoriaceum and linarin isolated from Buddleia cordata. Planta Med. 1998;64(2):134-137.

- Wilbur J. Final report of the safety assessment of Acacia catechu gum, Acacia concinna fruit extract, Acacia dealbata leaf extract,Acacia dealbata leaf wax, Acacia decurrens extract, Acacia farnesiana extract, Acacia farnesiana flower wax, Acacia farnesianagum, Acacia Senegal extract, Acacia senegal gum, and Acacia senegal gum extract. Int J Toxicol. 2005;24 (Suppl 3):75-118.