Scientific Name

Centella asiatica (L.) Urb.

Synonyms

Centella glochidiata (Benth.) Drude, Centella hirtella Nannf., Centella tussilaginifolia (Baker) Domin, Centella ulugurensis (Engl.) Domin, Centella uniflora (Colenso) Nannf., Chondrocarpus asiaticus Nutt., Chondrocarpus triflorus Nutt., Glyceria asiatica Nutt., Glyceria triflora Nutt., Hydrocotyle asiatica L., Hydrocotyle biflora P. Vell., Hydrocotyle brasiliensis Scheidw. ex Otto & F. Dietr., Hydrocotyle brevipedata St. Lager & St.-Lag., Hydrocotyle ficarifolia Stokes, Hydrocotyle ficarioides Lam., Hydrocotyle inaequipes DC., Hydrocotyle lurida Hance, Hydrocotyle nummularioides A. Rich., Hydrocotyle reniformis Walter, Hydrocotyle repanda Pers., Hydrocotyle sylvicola E. Jacob Cordemoy, Hydrocotyle triflora Ruiz & Pav., Hydrocotyle tussilaginifolia Baker, Hydrocotyle uniflora Colenso [1]

Vernacular Name

| Malaysia | Pegaga [2] |

| English | Asiatic pennywort, Indian pennywort, gotu-gotu [2] |

| China | Ji xui cao [3] |

| India | Vallarai (Tamil); brahma manduki, brahmi (Hindi); brahmi (Punjabi); manduki, darduracchada (Sanskrit); manimuni (Assamese); jholkhuri, thalkuri, thankuni (Bengali); khodabrahmi, khadbhrammi (Gujrati); ondelaga, brahmi soppu (Kannada); kodangal (Malayalam); karivana (Marathi); saraswati aku, vauari (Telugu); brahmi (Urdu) [4] |

| Indonesia | Daun kaki kuda, pegagan (General); antanan gede (Sundanese) [2] |

| Brunei | Pegaga [2] |

| Singapore | Pegaga [2] |

| Thailand | Bua bok (Central); pa-na-e khaa-doh (Karen, Mae Hong Son); phak waen (Peninsular) [2] |

| Laos | Phak nok [2] |

| Myanmar | Min-kuabin [2] |

| Philippines | Takip-ko-hol, tapingan-daga (Tagalog); hahang-halo (Bisaya) [2] |

| Cambodia | Trachiek kranh [2] |

| Vietnam | Rau m[as], t[is]ch tuy[ees]t th[ar]o [2] |

| France | Hydrocotyle asiatique [2]. |

Geographical Distributions

Centella asiatica is originated from Asian and East African regions such as India, Sri Lanka and Madagascar. It spreads out to many countries including Malaysia, Pakistan, China, Japan, East Africa, West Indies, South America and Australia. It is commonly found growing in wet areas near river banks and canals. Most species survive well in open areas while others need some shade. [5][6]

Botanical Description

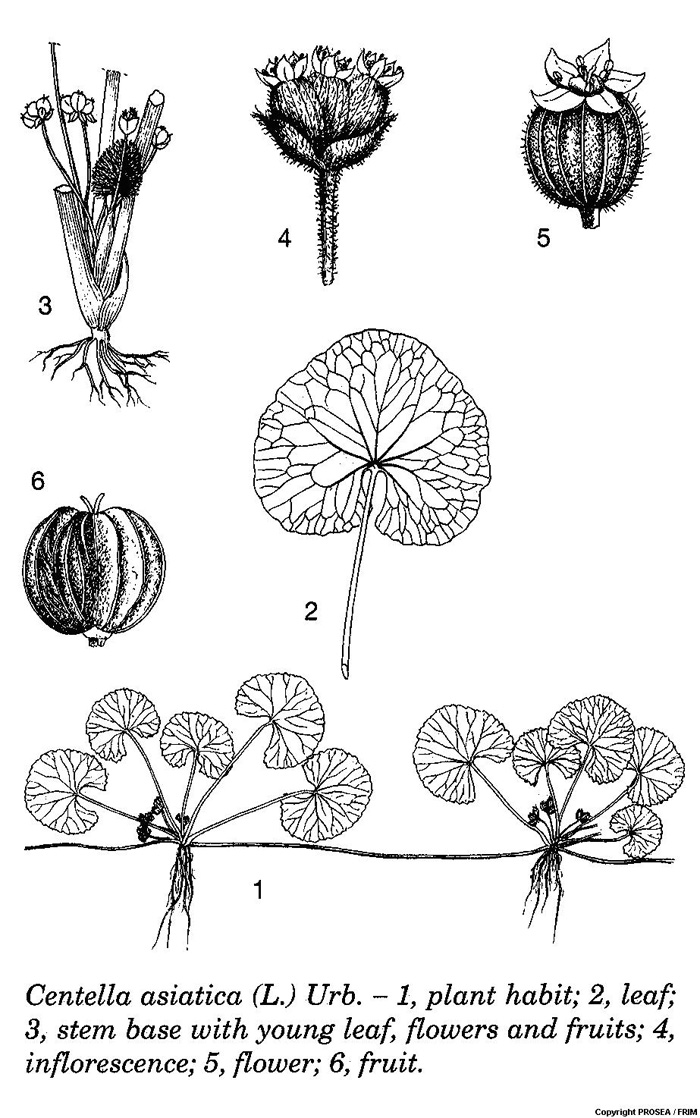

C. asiatica is a member of the family. It is a small perennial herb, creeping with long stolons up to 2.5 m long. The rooting system is at the nodes. Its young parts are more or less hairy. [2]

The leaves are in rosettes form and simple. The lamina is orbicular-reniform, 1-7 cm in diametre, regularly crenate or crenate-dentate, palmately veined and slightly smooth. Petiole is 40(-50) cm long, hairless to hairy, broadened at the base into a leaf-sheath. Stipules are absent. [2]

The inflorescence is an axillary simple umbel, (1-)3(-7)-flowered with sessile middle flower and lateral flowers are with a short pedicel and an involucre that consists of 2 ovate bracts with 0.5-5 cm long peduncles. Flowers are 5-merous bisexual. Sepal is obsolete. Petals are roundish to broadly obovate 1-1.5 mm long, entire, greenish, pinkish or reddish. The petals are 2-lobed disk and plane with elevated margin, arranged alternate with the stamens. The ovary is inferior, 2-celled and 2 styles. [2]

The fruit consists of 2 one-seeded mericarps connected by a narrow junction, separate when mature, oblate-rounded, strongly laterally compressed, 3 mm x 3-4 mm. Its mericarps are distinctly 7-9-ribbed; ribs connected by veins and hairy when young but often becoming hairless. [2]

The seed is laterally compressed. [2]

The seedling is with epigeal germination with 2-4 mm long hypocotyls and they are smooth. The cotyledons are broadly egg-shaped to elliptical, shallowly emarginated at apex and hairless. The epicotyl is absent. [2]

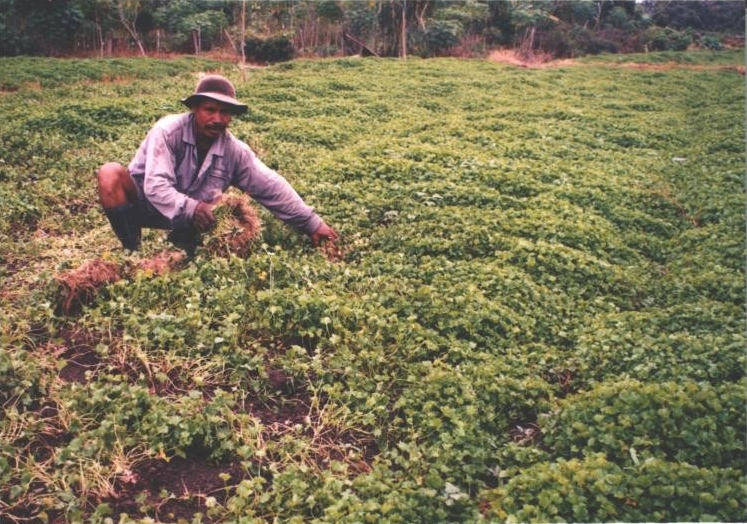

Cultivation

C. asiatica occurs in sunny or slightly shaded, damp localities, on fertile soils (preferring sandy loams with much organic mater), e.g. along stream banks, on or near paths, alongside walls and in damp, open grassland, from sea-level up to 2500 m altitude. It is an early coloniser of fallowed land in shifting cultivation systems, but may occur also on recently disturbed habitats and even on undisturbed sites. It may carpet the ground completely, but in regions with a monsoon climate, it is usually only during the rainy season. [2]

Soil Suitability and Climate Requirement

C. asiatica survives well on sandy loam to sandy clay. It also grows on other soil types as long as not too sandy or clayey. For commercial production, the soil has to be more friable for easy harvesting process. Good soil is friable, fertile with high organic matter and with good drainage. Generally, C. asiatica needs 2,000-3,000 mm of rain annually but not more than 100 mm per month. Dry period of more than two months is not suitable but irrigation is needed if planting is continued. Too much rain makes the crop susceptible to root rot. [5][6]

Field Preparation

Land Preparation

Good land preparation is very important for good crop growth. The area has to be ploughed once with a disk plough followed twice using a rotovator. [5][6]

Production of Planting Materials

C. asiatica or ‘pegaga’ is normally planted using mature vegetative materials consisting of stem, leaves and roots. Cultivar ‘pegaga nyonya’ can be planted using the splits consisting of 8-10 plantlets. It can be directly planted in the field. [5][6]

Field Planting

Planting bed has to be prepared before planting. It can be done manually or by using a rotovator. The planting bed is 1.5 m wide at the base and 1.0-1.2 m high at the topmost. The length depends on the requirement and the planting area. The plant spacing is 20 cm between rows and 20 cm between plants. These planting distances give population density of about 125,000 per hectare. Planting is done at the onset of rainy season. [5][6]

Field maintenance

Fertilisation

Organic and inorganic fertilisers are usually applied in C. asiatica cultivation. Chicken manure can be used as the source of organic fertiliser together with enriched organic fertiliser such as complehumus (NPKTe: 8-8-8-3). When using chicken manure alone, 8.5 t/ha is applied 4-5 days before planting as basal fertiliser followed by 3.5 t/ha applied one month after planting. When combination of chicken manure and enriched organic fertiliser is used, a rate of 1.5 t/ha of chicken manure and 5 t/ha enriched organic fertiliser is applied as basal fertiliser. This is followed by 1.5 t/ha enriched organic fertiliser applied one month after planting. [5][6]

Weed Control

It is recommended to spray pre-emergence weedicide to hinder the germination of weed seeds after C. asiatica is sown. Three to four times of manual weeding is required until the canopy covers the bed fully. Weeding is then no longer required. Mulching using plastic or rice straw/dried lalang at the early stage of growth helps to control weeds efficiently as well as saves energy and cost due to manual weeding. [5][6]

Water management

Sufficient water supply is needed for C. asiatica cultivation. C. asiatica is short-rooted plants where the roots are found near the soil surface. Irrigation is crucial during the first two weeks after planting. Watering is needed once in 2-3 days after two weeks of planting. A micro-sprinkler irrigation system is recommended for C. asiatica. [5][6]

Pest and Disease Control

The most common diseases are bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum and root rot by Sclerotia. This occurs when the environment is too damp. To control these diseases, the plant has to be pulled out and removed to avoid spreading to other plants. Insect pests that usually attack C. asiatica are leaf hopper and white fly. [5][6]

Harvesting

C. asiatica is harvested six times (main crop and five ratoon crops) within one year of planting. The main crop of cultivar ‘pegaga nyonya’ is harvested 80-90 days after field planting. Each ratoon crop is harvested every 50-60 days after the first harvest. The average fresh yield of cultivar ‘pegaga nyonya’ for both main harvest and ratoon crops is 20 t/ha. [5][6][7]

Postharvest handling

Harvested C. asiatica should be cleaned by using running water. For fresh market, it is bundled at one kilogramme each. C. asiatica harvested for making herbal tea or for extraction of active ingredients, the plant materials are dried in a drier at temperature of 40oC. [5][6]

Estimated cost of production

The total input cost is RM5,300-RM35,500. High input cost is during the main crop but the cost reduces during ratoon crop. The high cost is due to the cost of planting materials of about RM22,800 for the main crop. No costs incurred in the ratoon crop. The labour cost is RM4,500-RM10,800. The average cost of production (for main and ratoon crop) is RM20,355. With the fresh yield averaging 20 t/ha at every harvest, the production is RM0.97/kg. The production cost was estimated based on the cost of current inputs during writing of this article. [5][6][7]

Chemical Constituent

Water extract of C. asiatica has been found to contain centellosides D-E, pectin and acidic arabinogalactan. [8][9][10]

The ethanol extract had triterpenes (e.g. 2α,3β,20,23-tetrahydroxyurs-28-oic acid, 2α,3β,23-trihydroxyurs-20-en-28-oic acid), triterpenoid glycosides (e.g. asiaticoside, asiaticosides A-F, madecassoside, scheffuroside B) and a saponin (e.g. 2α,3β,23-trihydroxyurs-20-en-28-oic acid-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl -(1→6)-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester). [11][12][13][14] The methanol extract had triterpenes and triterpenoids (e.g. ursolic acid lactone, ursolic acid, pomolic acid, 2α,3α-dihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-epimaslinic acid, corosolic acid, asiaticoside, madecassoside, asiatic acid, 6β-hydroxyasiatic acid, 3-O-[a-L-arabinopyranosyl]-2α,3β,6β,23-a-tetrahydroxyurs-12-ene-28-oic acid), a phenolic (e.g. rosmarinic acid), a steroid (e.g. b-sitosterol 3-O-b-glucopyranoside) and others (e.g. 8-acetoxy-1,9-pentadecadiene-4,6-diyn-3-ol, centellin, asiaticin, centellicin) [15][16][17][18]. The methanol-water extract had phenolics (e.g. castilliferol, castillicetin, isochlorogenic acid) [19].

C. asiatica has also been reported to contain brahmic acid, 3β-6β-23-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3β-6β-23-trihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid, α-terpinene, thymol methyl ether, sceffoleoside A, bayogenin, centellasaponins B-D, centellose, D-gulonic acid, meso-inositol, docosyl ferulates) [20][21][22][23][24]. In addition, its cell cultures had irbic acid, chlorogenic acid and triferulic acid [25].

Active principles of C. asiatica have been reported as pentacyclic tirterpenes, (e.g. asiatic acid, asiaticoside, madecassic acid and madecassoside). [26]

Plant Part Used

Aerial parts, whole plant. [27]

Traditional Use

C. asiatica is traditionally used for albinism, anemia, asthma, bronchitis, cellulite, cholera, constipation, dermatitis, diarrhea, dizziness, dysentery, dysmenorrhea, dysuria, epistaxis, epilepsy, haematemesis, hemorrhoids, hepatitis, hypertension, jaundice, leucorrhoea, nephritis, nervous disorders, neuralgia, measles, rheumatism, smallpox, syphilis, toothache, urethritis and varices. It is also used as an antipyretic, anti-inflammatory and a “brain tonic” [28][29][30]. Poultices of C. asiatica have been used to treat contusions, closed fractures, sprains and furunculosis [30].

Preclinical Data

Pharmacology

Cytotoxic and antitumour activity

Methanol (80%) extract and acetone fraction of methanol (80%) extract of C. asiatica whole plant inhibited proliferation of Ehrlich ascites tumour cells (concentration of 50% cell death 62 and 17 μg/mL, respectively) and Dalton’s lymphoma ascites tumour cells (75 and 22 μg/mL, respectively). The acetone fraction also suppressed multiplication of mouse lung fibroblast (L-929) cells at a concentration of 50% cell death of 8 μg/mL. Both the crude extract and the acetone fraction of C. asiatica significantly reduced the development of murine solid tumours when administered simultaneously with tumour transplantations or given 10 days prior to tumour transplantation. The latter finding suggested a mechanism which involves stimulation of the immune system. The crude methanol extract (1 mg/g body weight) also significantly (p < 0.001) reduced ascites tumour growth and increased the life span of Ehrlich ascites tumour bearing mice. The mechanism may involved inhibition of DNA synthesis. [31]

Methanol (80%) extract of C. asiatica whole plant exhibited concentration dependent cytotoxicity towards human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by apoptosis with LD50 value of 66 mg. Asiatic acid (10 µM) was found to kill ~95% cells. [32]

Antigenotoxicity activity

The extract of C. asiatica also regulates the genotoxicity which will lead to the protection of human lymphocytes. [33]

Wound healing activity

Titrated extract of C. asiatica plant that constituted of asiatic acid, madecassic acid and asiaticoside (40 mg) injected to male Sprague-Dawley rats twice a week for 4 weeks had wound healing effect by stimulation of glycogen and glycosaminoglycan synthesis and fasten the new formation of connective tissue. [34]

A laboratory animal study reported that various formulations (ointment, cream, and gel) of an aqueous extract of gotu kola applied to open wounds in rats (applied topically 3 times daily for 24 days) with the result of increased cellular proliferation and collagen synthesis at the wound site, as shown by an increase in collagen content and tensile strength. It was found that the C. asiatica treated wounds epithelialized faster and the rate of wound contraction was higher when compared to the control wounds. Healing was more prominent with the gel product [35]. It is believed to have an effect on keratinization, which aids in thickening skin in areas of infection [36].

A formulation with C. asiatica plant extract induced proliferation of granulation tissue and increased tensile strength when applied locally on wounds in rats and decreased the area of skin necrosis caused by burns [37]. The plant also purportedly reduced scarring and stimulated skin growth by acting on the production of collagen fibres by fibroblasts and resulted in a decrease in the inflammatory reaction and myofibroblast production [38].

Asiaticoside which is one of the C. asiatica constituents has been reported to possess wound healing activity by increasing collagen formation and angiogenesis [39][40]. In a laboratory animal study, the effects of asiaticoside on antioxidant levels was examined, as antioxidants have been reported to play a role in the wound healing process. It was concluded that asiaticosides may enhance induction of antioxidants at an initial stage of wound healing, but continued application of the preparation seem not to increase the antioxidant levels in wound healing [41]. C. asiatica may assist in the maintenance of connective tissue. In the treatment of scleroderma, gotu kola C. asiatica may also assist in stabilizing connective tissue growth, reducing its formation [42].

Antigastric activity

Aqueous extract of C. asiatica (0.05, 0.25 and 0.50 g/kg) significantly inhibited ethanol-induced gastric lesions and decreased mucosal myeloperoxidase in a dose dependent manner when the extract was given before ethanol administration. These results suggest that C. asiatica protected the gastric mucosa by improving the integrity of the mucosal lining while reduction of myeloperoxidase and gastric lesions could be due to a decrease in the recruitment of neutrophils by C. asiatica or to its free radical scavenging activity [43].

The water extract of C. asiatica whole plant (0.10 and 0.25 g/kg) and asiaticoside (5 and 10 mg/kg) given orally for 7 days to male Sprague-Dawley rats with acetic acid induced gastric ulcers were found to decrease the ulcer sizes (p< 0.01). This was due to the reduction of myeloperoxidase activity (p< 0.01) and promotion of epithelial cell proliferation (p<0.01) by upregulated expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in the ulcer tissues [44]. The extract and asiaticoside also inhibited inducible nitric oxide synthase activity (p< 0.01) and protein expression at the ulcer tissues [45].

Radioprotective activity

The aqueous extract of C. asiatica whole plant (100 mg/kg body weight) given orally to 6-8 weeks old Swiss Albino mice irradiated with Co-60 gamma radiation was reported to significantly increase survival time. [46]

Antimicrobial activity

Antibacterial

Essential oil of C. asiatica showed a broad spectrum of antibacterial activities against Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella sonnei) organisms. Activity against Gram-positive bacteria was greater than against Gram-negatives. Germacrene compounds in the essential oil are known to be strong antimicrobial and antitumour agents. [47]

Antiviral

In vitro study of aqueous extract of C. asiatica showed intracellular activities against Herpes Simplex Viruses, containing both anti-HSV-1 and –2 activities. [48]

Antioxidant activity

Ethanol extracts of all plant parts (leaves, petioles and roots) of C. asiatica showed significant antioxidant activity (p<0.05) in the concentration range of 1000-3000 ppm. [49]

Methanol extract of C. asiatica whole plant (50 mg/kg/day) administered orally to 2-month old lymphoma-bearing male Swiss mice for 14 days significantly increased the antioxidant enzymes of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase, as well as the glutathione and ascorbic acid antioxidants in the liver and kidney. [50]

C. asiatica extract (0.3%) and powder (5%) reduced oxidative stress when given to H2O2-exposed rats for 25 weeks. There was a reduction in erythrocyte malondialdehyde levels as well as a decrease in the superoxide dismutase activity of these rats given C. asiatica although the catalase activities were higher than in the H2O2-fed rats. [51]

Aqueous extract of C. asiatica was shown to be able to improve oxidative stress by being a neuroprotective as well as regulate endogenously. [52]

Neuropharmacology activity

Several laboratory studies have found that C. asiatica extracts help decrease cognitive impairment in rat models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and stimulating property on neuronal dendrites of hippocampal region. The mechanism of neuroprotection includes enhancement of the phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) and inhibition of ERK/RSK signaling pathway. [53]

Aqueous extract of C. asiatica whole plant (300 mg/kg) given to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced neurotoxicity in aged Sprague-Dawley rats for 21 days protected the brain against neurodegenerative disorders with reference to examination of the oxidative biomarker levels in corpus striatum and hippocampus homogenate. [54]

Hydroalcoholic extract of C. asiatica leaves possesses potential anticonvulsant, antioxidant and central nervous system (CNS) depressant actions. The extract (100 mg/kg) showed 50% protection while a higher dose (200 mg/kg) completely protected against pentylenetetrazol-induced convulsions in rats. The extract also protected against convulsions induced by an increase in current electroshock and by strychnine. Spontaneous motor activity was reduced while diazepam withdrawal-induced autonomic hyperactivity was potentiated as was the pentobarbitone sleeping time in mice. The extract (100-150 mg/kg) significantly reduced the normal body temperature of mice, while in brain homogenates it (1.3-40 mg/mL) reduced the formation of lipid peroxidation products. [55]

Aqueous extract of C. asiatica (100-300 mg/kg) was able to prevent cognitive deficits in intracerebroventricular streptozotocin-induced cognitive impairment in rats after 14 and 21 days indicating improved acquisition and retention of memory. These doses of C. asiatica did not affect spontaneous locomotor activity in these rats thus excluding the possibility that the CNS depressant/stimulant activity of the herb had contributed to the changes in the passive avoidance and elevated plus maze tests. After 21 days of treatment in the same groups of rats, the extract (200 & 300 mg/kg) significantly reduced brain malondialdehyde levels and increased brain glutathione levels without affecting brain superoxide dismutase activity while brain catalase levels were increased by the highest dose of the extract (300 mg/kg). [56]

The asiaticoside constituent of C. asiatica showed phospholipase A enzymes inhibition in the brain. [57]

Anxiolytic activity

The triterpine contents in C. asiatica extract showed anxiolytic activity and there are possibility of synergistic effect between terpene and asiaticoside. [58]

Toxicity

Aqueous extract of C. asiatica (5 mg/plate) lack cytotoxicity and mutagenicity on Salmonella typhimurium TA98 or TA100 with or without S9 mixture [59]. Acetone fraction of C. asiatica extract did not induce cytotoxicity in normal human lymphocytes at a 50 µg/mL. Oral administration the crude extract and the acetone fraction of C. asiatica to normal and tumour bearing mice at maximal concentrations of 500 mg/mouse did not produce any toxic symptoms while the body weights of the mice were increased [31].

Acute toxicity

Oral single dose acute toxicity study of aqueous mixture of C. asiatica whole plant powder on female Sprague Dawley rats (aged between 8 and 12 weeks old) showed no toxic effects on the parameters observed, including behaviors, body weight, food and water intake. All rats were observed for 14 days prior to necropsy. No death was found throughout the study period. Necropsy revealed no significant abnormality. LD50 value was determined as > 2000 mg/kg. [60]

Clinical Data

Poisonous Management

No documentation.

Line Drawing

References

- The Plant List. Ver1.1. Centella asiatica L. [homepage on the Internet]. c2013 [updated 2012 Apr 18; cited 2016 Oct 05]. Available from: http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-2708815

- Hargono D, Lastari P, Astuti Y, van den Bergh MH. Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. In: de Padua LS, Bunyapraphatsara N, Lemmens RHMJ, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 12(1): Medicinal and poisonous plants 1. Leiden, Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers, 1999; p. 190-194.

- Chinese-English manual of common-used in traditional Chinese medicine. China: Joint Publishing Co. & Guangdong Science & Technology, 1992; p. 704.

- The Ayurvedic pharmacopoeia of India. Part I, Volume IV. New Delhi: Department of Ayush, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2004; p. 69. [cited 2012 Dec 09]. Available from http://www.ayurveda.hu/api/API-Vol-4.pdf

- Zainal Abidin H, Kamaruddin H. Pegaga (Centella asiatica). In: Musa Y, Muhammad Ghawas M, Mansor P, editors. Penanaman tumbuhan ubatan & beraroma. Serdang, Selangor: MARDI 2005; p. 70-76.

- Zainal Abidin H, Kamaruddin H. Manual teknologi penananaman pegaga. Serdang, Selangor: MARDI; 2005.

- Zainal Abidin H, Muhammad Ghawas M, Mansor P. Turning pegaga (Centella asiatica) and pandan wangi (Pandanus odorus) into cash. Proposal presented at NATPRO 2003, Asia Pacific Natural Products Expo. 2003 Apr 10-12. Putra World Trade Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2003.

- Weng XX, Zhang J, Gao W, Cheng L, Shao Y, Kong DY. Two new pentacyclic triterpenoids from Centella asiatica. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2012;95(2):255-260.

- Wang XS, Dong Q, Zuo JP, Fang JN. Structure and potential immunological activity of a pectin from Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338(22):2393-2402.

- Wang XS, Zheng Y, Zuo JP, Fang JN. Structural features of an immunoactive acidic arabinogalactan from Centella asiatica. Carbohydr Polym. 2005;59(3):281-288.

- Yu QL, Duan HQ, Takaishi Y, Gao WY. A novel triterpene from Centella asiatica. Molecules. 2006;11(9):661-665.

- Yu QL, Duan HQ, Gao WY, Takaishi Y. A new triterpene and a saponin from Centella asiatica. Chin Chem Lett. 2007;18(1):62-64.

- Jiang ZY, Zhang XM, Zhou J, Chen JJ. New triterpenoid glycosides from Centella asiatica. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2005;88(2):297-303.

- Sahu NP, Roy SK, Mahato SB. Spectroscopic determination of structures of triterpenoid trisaccharides from Centella asiatica. Phytochemistry. 1989;28(10):2852-2854.

- Thomas MT, Kurup R, Johnson AJ, et al. Elite genotypes/chemotypes, with high contents of madecassoside and asiaticoside, from sixty accessions of Centella asiatica of South India and the Andaman Islands: for cultivation and utility in cosmetic and herbal drug applications. Ind Crops Prod. 2010;32(3):545-550.

- Yoshida M, Fuchigami M, Nagao T, Okabe H, Matsunaga K, Takata J, Karube Y, Tsuchihashi R, Kinjo J, Mihashi K, Fujioka T. Antiproliferative constituents from Umbelliferae plants VII. Active triterpenes and rosmarinic acid from Centella asiatica. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(1):173-175.

- Shukla YN, Srivastava R, Tripathi AK, Prajapati V. Characterization of an ursane triterpenoid from Centella asiatica with growth inhibitory activity against Spilarctia obliqua. Pharm Biol. 2000;38(4):262-267.

- Siddiqui BS, Aslam H, Ali ST, Khan S, Begum S. Chemical constituents of Centella asiatica. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2007;9(4):407-414.

- Subban R, Veerakumar A, Manimaran R, Hashim KM, Balachandran I. Two new flavonoids from Centella asiatica (Linn.). J Nat Med. 2008;62(3):369-373.

- Singh B, Rastogi RP. Chemical examination of Centella asiatica Linn – III: constitution of brahmic acid. Phytochemistry. 1968;7(8):1385-1393.

- Singh B, Rastogi RP. A reinvestigation of the triterpenes of Centella asiatica. Phytochemistry. 1969;8(5):917-921.

- Asakawa Y, Matsuda R, Takemoto T. Mono- and sesquiterpenoids from Hydrocotyle and Centella species. Phytochemistry. 1982;21(10):2590-2592.

- Yu QL, Gao WY, Zhang YW, Teng J, Duan HQ. Studies on chemical constituents in herb of Centella asiatica. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2007;32(12):1182-1184. Chinese.

- Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Ueda H, Yoshikawa M. Medicinal foodstuffs. XXVII. Saponin constituents of gotu kola (2): Structures of new ursane- and oleanane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, centellasaponins B, C, and D, from Centella asiatica cultivated in Sri Lanka. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2001;49(10):1368-1371.

- Antognoni F, Perellino NC, Crippa S, et al. Irbic acid, a dicaffeoylquinic acid derivative from Centella asiatica cell cultures. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(7):950-954.

- Inamdar PK, Yeole RD, Ghogare AB and de Souza NJ. Determination of biologically active constituents in Centella asiatica. J Chromatogr A. 1996;742(1-2):127-130

- Malaysian Herbal Monograph Committee. Malaysian Herbal Monograph 2015. Kuala Lumpur: Institute for Medical Research, 2015; p. 50.

- The Indian pharmaceutical codex. Volume I. Indigenous drugs. New Delhi: Council of Scientific & Industrial Research; 1953.

- British herbal pharmacopoeia. Part 2. Exeter, Devon: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1979.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Institute of Materia Medica Hanoi. Medicinal Plants in Viet Nam. Manila: World Health Organization-Regional Office for the Western Pacific/Institute of Materia Medica Hanoi; 1990.

- Babu TD, Kuttan G, Padikkala J. Cytotoxic and anti-tumour properties of certain taxa of Umbelliferae with special reference to Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;48(1):53-57.

- Babykutty S, Padikkala J, Sathiadevan PP, Vijayakurup V, Azis TK, Srinivas P, Srivanas G. Apoptosis induction of Centella asiatica on human breast cancer cells. Afr J Trad Complement Altern Med. 2008;6(1):9-16.

- Siddique YH, Ara G, Beg T, Faisal M, Ahmad M, Afzal M. Antigenotoxic role of Centella asiatica L. extract against cyproterone acetate induced genotoxic damage in cultured human lymphocytes. Toxicol in Vitro. 2008;1(22):10-17.

- Maquart FX, Chastang F, Simeon A, Birembaut P, Gillery P, Wegrowski Y. Triterpenes from Centella asiatica stimulate extracellular matrix accumulation in rat experimental wounds. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9(4):289-296.

- Sunilkumar, Parameshwarajah S, Shivakumar HG. Evaluation of topical formulations of aqueous extract of Centella asiatica on open wounds in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1998;36(6):569-572.

- Poizot A, Dumez D. [Modification of the kinetics of healing after iterative exeresis in the rat. Action of a triterpenoid and its derivatives on the duration of healing]. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1978;286(10):789-792. French.

- Vogel HG, De Souza NJ and D’sa A. Effects of terpenoids isolated from Centella asiatica of granuloma tissue. Acta Ther. 1990;16(4):285-298.

- Ortiz KJ and Yiannias JA. Contact dermatitis to cosmetics, fragrances and botanicals. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(3):264-271.

- Rosen H, Blumenthal A, McCallum J. Effect of asiaticoside on wound healing in the rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1967;125(1):279-280.

- Kimura Y, Sumiyoshi M, Samukawa K, Satake N, Sakanaka M. Facilitating action of asiaticoside at low doses on burn wound repair and its mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;584(2-3):415-423.

- Shukla A, Rasik AM, Dhawan BN. Asiaticoside-induced elevation of antioxidant levels in healing wounds. Phytother Res. 1999;13(1):50-54.

- Tenni R, Zanaboni G, De Agostini MP, Rossi A, Bendotti C, Cetta G. Effect of the triterpenoid fraction of Centella asiatica on macromolecules of the connective matrix in human skin fibroblast cultures. Ital J Biochem. 1988;37(2):69-77.

- Cheng CL, Koo MW. Effects of Centella asiatica on ethanol induced gastric mucosal lesions in rats. Life Sci. 2000;67(21):2647-2653.

- Cheng CL, Guo JS, Luk J and Koo MW. The healing effects of Centella extract and asiaticoside on acetic acid induced gastric ulcers in rats. Life Sci. 2004; 74(18): 2237-2249.

- Guo JS, Cheng CL, Koo MW. Inhibitory effects of Centella asiatica water extract and asiaticoside on inducible nitric oxide synthase during gastric ulcer healing in rats. Planta Med. 2004;70(12):1150-1154.

- Sharma J, Sharma R. Radioprotection of Swiss albino mouse by Centella asiatica extract. Phytother Res. 2002;16(8):785-786.

- Oyedeji OA and Afolayan AJ. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil of Centella asiatica growing in South Africa. Pharm Biol. 2005;43(3):249-252.

- Yoosook C, Bunyapraphatsara N, Boonyakiat Y, et al. Anti-Herpes Simplex Virus activities of crude water extracts of Thai medicinal plants. Phytomedicine. 2000;6(6):411-419.

- Hamid AA, Shah ZM, Muse R, Mohamed S. Characterisation of antioxidative activities of various extracts of Centella asiatica (L) Urban. Food Chem. 2002;77(4):465-469.

- Jayashree G, Kurup Muraleedhara G, Sudarslal S, Jacob VB. Anti-oxidant activity of Centella asiatica on lymphoma-bearing mice. Fitoterapia. 2003;74(5):431-434.

- Hussin M, Abdul-Hamid A, Mohamad S, Saari N, Ismail M, Bejo MH. Protective effect of Centella asiatica extract and powder on oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem. 2007;100(2):535-541.

- Shinomol GK. Effect of Centella asiatica leaf powder on oxidative markers in brain regions of prepubertal mice in vivo and its in vitro efficacy to ameliorate 3-NPA-induced oxidative stress in mitochondria. Phytomedicine. 2008;15(11):971-984.

- Xu Y, Cao Z, Khan I, Luo Y. Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica) extract enhances phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein in neuroblastoma cells expressing amyloid beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13(3):341-349.

- Haleagrahara N, Ponnusamy K. Neuroprotective effect of Centella asiatica extract (CAE) on experimentally induced parkinsonism in aged Sprague-Dawley rats. Journal of Toxicology Sciences. 2010;35(1):41-47.

- Ganachari MS, Babu SVV and Katare SS. Neuropharmacology of an extract derived from Centella asiatica. Pharm Biol. 2004;42(3):246-252.

- Kumar MHV and Gupta YK. Effect of Centella asiatica on cognition and oxidative stress in an intracerebroventricular streptozotocin model of Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003;30(5-6):336-342.

- Barbosa NR, Pittella F, Gattaz WF. Centella asiatica water extract inhibits iPLA2 and cPLA2 activities in rat cerebellum. Phytomedicine. 2008;10(15):896-900.

- Wijeweera P, Arnason JT, Koszycki D, Merali Z. Evaluation of anxiolytic properties of Gotukola–(Centella asiatica) extracts and asiaticoside in rat behavioral models. Phytomedicine. 2006;9-10(13):668-676.

- Yen GC, Chen HY, Peng HH. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity, mutagenicity and antimutagenicity of emerging edible plants. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39(11):1045-1053.

- Teh BP, Hamzah NF, Rosli SNS, Yahaya MAF, Zakiah I, Murizal Z. Acute oral toxicity study of selected Malaysian medicinal herbs On Sprague Dawley rats. Kuala Lumpur: Institute for Medical Research, Ministry of Health; 2012. Report No .: HMRC 11-045/01/CA/WP/P.

- Sastravaha G, Yotnuengnit P, Booncong P, Sangtherapitikul P. Adjunctive periodontal treatment with Centella asiatica and Punica granatum extracts. A preliminary study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2003; 5(4):106-115.

- Tholon L, Neliat G, Chesne C, Saboureau D, Perrier E, Branka JE. An in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo demonstration of the lipolytic effect of slimming liposomes: An unexpected alpha(2)-adrenergic antagonism . J Cosmet Sci. 2002;53(4):209-218.

- Cesarone MR, Incandela L, De Sanctis MT, et al. Evaluation of treatment of diabetic microangiopathy with total triterpenic fraction of Centella asiatica: A clinical prospective randomized trial with a microcirculatory model. Angiology. 2001;52(2):S49-54.

- Wattanathorn J, Mator L, Muchimapura S, et al. Positive modulation of cognition and mood in the healthy elderly volunteer following the administration of Centella asiatica. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116(2):325-332.

- Young GL, Jewell D. Creams for preventing stretch marks in pregnancy. [Cochrane review] In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 1996. Art No.: CD000066.

- Widgerow AD, Chait LA, Stals R, Stals PJ. New innovations in scar management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24(3):227-234.

- Bradwejn J, Zhou Y, Koszycki D, Shlik J. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of gotu kola (Centella asiatica) on acoustic startle response in healthy subjects. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(6):680-684.

- Darnis F, Orcel L, de Saint-Maur PP, Mamou P. [Use of a titrated extract of Centella asiatica in chronic hepatic disorders]. Sem Hop. 1979;55(37-38):1749-1750. French.

- Allegra C. [Comparative capillaroscopic study of certain bioflavonoids and total triterpenic fractions of Centella asiatica in venous insufficiency]. Clin Ter. 1984;110(6):555. Italian.

- Cesarone MR, Laurora G, De Sanctis MT, Belcaro G. Activity of Centella asiatica in venous insufficiency. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1992;40(4):137-143.

- Cesarone MR, Laurora G, De Sanctis MT, et al. The microcirculatory activity of Centella asiatica in venous insufficiency. A double-blind study. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1994;42(6):299-304.

- Belcaro GV, Grimaldi R, Guidi G. Improvement of capillary permeability in patients with venous hypertension after treatment with TTFCA. Angiology. 1990;41(7):533-540.

- De Sanctis MT, Incandela L, Cesarone MR, Grimaldi R, Belcaro G, Marelli C. Acute effects of TTFCA on capillary filtration in severe venous hypertension. Panminerva Med. 1994;36(2):87-90.

- Izu R, Aguirre A, Gil N, Diaz-Perez JL. Allergic contact dermatitis from a cream containing Centella asiatica extract. Contact Dermatitis. 1992,26(3):192-193.

- 52 Danese P, Carnevali C, Bertazzoni MG. Allergic contact dermatitis due to Centella asiatica extract. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31(3):201.

- ESCOP (European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy), editor. ESCOP Monographs. The scientific foundation for herbal medicinal products. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag, 2003; p. 37.

- Eun HC, Lee AY. Contact dermatitis due to madecassol. Contact Dematitis. 1985;13(5):310-313.

- Bilbao I, Agiurre A, Zabala R, Gonzalez R, Raton J, Diaz Perez JL. Allergic contact dermatitis from butoxyethyl nicotinic acid and Centella asiatica extract. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33(6):435-436.

- Hausen BM. Centella asiatica (Indian Pennywort), an effective therapeutic but a weak sensitizer. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29(4):175-179.

- Jorge OA, Jorge AD. [Hepatotoxicity associated with the ingestion of Centella asiatica]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97(2):115-124. Spanish.

- Iwu MM. Handbook of African medicinal plants. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1993.

- Standard of ASEAN herbal medicine. Volume 1. Jakarta: ASEAN Countries, 1993; p. 152.