7.1 INTRODUCTION

Local communities have always generated particular traditional knowledge which has been practiced for shorter and longer periods and informally passed from generation to generation or from group to group [1]. The World Health Organization estimates that the majority of people in most non-industrial countries still relied on traditional forms of medicine for everyday health care [2]. Traditional health practices are based on world views or cosmologies that take up into account mental, social, spiritual, physical and ecological dimensions of health and well-being [2]. Thus, the conservation of traditional knowledge has long been of central importance to the concept of balance within the individual, and between the individual, society and nature [2].

Traditional knowledge was developed from experience gained over time and adapted to a local culture and environment. It has always played, and still plays an important role in the daily lives of the majority of people globally, and is considered to be an essential part of cultural identity [1]. It is vital to the health, and food security of millions of people in both the developing and developed world. In the developing countries, traditional medicines provide the only affordable treatment available to the poor. Knowledge of the healing properties of certain plants has been the source of many modern medicines, and modern health practices.

It has been acknowledged that over time, groups of people mainly in rural areas become familiar and build a way of doing things using their knowledge of agriculture, food harvesting and related purposes, and traditional medicine, as economic and subsistence activities. They are commonly a part of the similar ethnic and cultural group that form the national majority but have established adaptations of knowledge that are considered to be important to defend and preserve [3].

The proliferation of issues such as in-situ conservation, indigenous and traditional knowledge, genetic resources, benefit sharing, biotechnology, impact assessment and technology transfer are the chief mechanisms for the construction of concepts and objects of study in an ethnographic perspective within the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)-centered network [4]. A key process to be examined from such an ethnographic perspective is the growing participation of NGOs and social movements. However, it is undeniable that local communities’ participation and contributions are also important to support conservation efforts especially with regard to traditional knowledge of traditional medicines. Therefore, this research was conducted to identify conservation practices amongtraditional medicine practitionersin selected areas in Sabah.

7.2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

There are two concepts that must be defined in order to understand conservation of traditional knowledge, namely: CONSERVATION and TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE.

7.2.1 Conservation through a Participatory Approach

Conservation is an important issue within biodiversity debates. Strategies for conservation in biodiversity networking are based on an intervention model, which is related to the sustainable use of resources at international, national, and local levels. [4][5] Conservation can be an in-situ and ex-situ mechanism for management of resources [4]. The effectiveness of conservation efforts will depend on how partners work within a strategic framework through coordinated legislation, policies, strategies and programmes. Struggles and negotiations over models of nature and social practice among the groups involved will also affect the resulting policies of conservation and sustainable resources. The ethnography of the Colombian case for example, suggests that social movements can affect considerably the outcome of national conservation policies [4].

Recent trends in conservation are weighted toward participatory, inclusive, and community-based approaches [5]. One of the ways to conserve traditional knowledge and foster interest among the younger generations is via the establishment of learning centres such as traditional medicine gardens [6]. Community forestry activities under e-European Commission – United Nations Development Programme (EC-UNDP) for example, several medicinal gardens in Sabah has successfully established from 2004 to 2007. The purpose of these centres is to disseminate traditional knowledge especially on the topic of herbal-based healthcare. Indigenous tree nursery for local communities has also been designed as capacity building activities [6].

Studies relating to the documentation, ownership, and inclusion of traditional knowledge by Ma Rhea [3] highlight the important role played by education in the preservation, and maintenance of knowledge of indigenous peoples and local communities. It is only right that people should be able to undertake conservation and resource sustainability practices, and to use education to maintain their traditional knowledge. It should also be acknowledged that this knowledge is owned by them. Adult education is employed to support capacity building measures in indigenous and local communities [3]. Community-based adult education programs that undertake a variety of activities are needed, such as those that entail working with local communities to protect, promote and facilitate the use of their knowledge for conservation. Sometimes these education activities, also called community capacity building programs, draw on documented traditional knowledge, and the activity itself seeks to document, register and establish ownership of this knowledge. Documentation strengthens the capacity of indigenous communities to participate in the conservation management of their own resources [3].

The concept of conservation is mainly related to sustainability issues [4][5] preservation and maintenance [3] resources or treasure and something that can be inherited [7]. All terms are used to understand the concept of conservation in the context of this study.

7.2.2 The Definition of Traditional Knowledge: An overview

The terms, “local knowledge”, “indigenous knowledge” and “traditional ecological knowledge” are sometimes used by various commentators as synonyms for “traditional knowledge” [8]. Conceptually, “knowledge” means the accumulated body of information that may be said to form a worldview [8]. Tradition-based refers to knowledge systems, creations, innovations and cultural expressions which have generally been transmitted from generation to generation. [9] It is also regarded as pertaining to a particular people or its territory and constantly evolving in response to a changing environment [9]. Traditional, therefore, does not necessarily mean that the knowledge is ancient or static; but it is also representative of the cultural values of a people and thus is generally held collectively and not limited to any specific field of technology or the arts [9].

Traditional knowledge generally refers to the knowledge, skills, innovations, practices and values of indigenous or local communities acquired outside the formal education system through experience, observation, from the land or from spiritual teachings and handed down from one generation to another. [1][7][8] Traditional knowledge is well known as a set of practices through arts and crafts relating to plants, animals, microorganisms and other forms of life [10]. It is also the basis for the decision-making of communities on food security, human and animal health, education and natural resource management. The nature of traditional knowledge is such that it is transmitted orally rather than written down [1].

Characteristically, traditional knowledge is thus knowledge that is traditional only to the extent that its creation and use are part of the cultural traditions of a community and usually it is considered a collective knowledge. [1][9] The term traditional knowledge encompasses agriculture, science, technology, ecology, medicine, biodiversity, “expressions of folklore”, and elements of languages and movable cultural properties of knowledge [7]. Excluded from this description of traditional knowledge would be items not resulting from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary or artistic fields, such as human remains, languages in general and other similar elements of “heritage in the broad sense [7].

In this context, therefore, the definition of traditional knowledge advocated by Wenzel [8] O’Connor [1] and Smallacombe et al. [7], i.e. traditional knowledge relates to the knowledge, practices and values of indigenous or local communities, is of particular value in interpreting the traditional knowledge of medicinal plants.

7.3 THE CONSERVATION OF TRADITIONAL MEDICINE KNOWLEDGE IN SABAH

Based on primary and secondary data retrieved from literature reviews and fieldwork, some efforts to conserve traditional knowledge on medicinal plants – mainly from government, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) and local communities – are still ongoing. Initiatives by practitioners and the local communities have helped to conserve traditional knowledge on medicinal plants. Increasing awareness and the level of participation in conservation initiatives are two ways of protecting and preserving local knowledge. This study examines knowledge conservation practices among traditional medicine practitioners in Sabah. The areas selected are Binsulok village, Tuaran; Limbuak Darat and Batu Layar village, Banggi Island, Kudat; Narambai village, Ranau and Sukau and Bilit Village in Kinabatangan. This study represents the pattern and general picture of Sabah Traditional Medicine Knowledge.

7.3.1 Traditional Medicine Knowledge and Practices

Fieldwork is taking into account traditional medicine practices among indigenous and local communities through interviews with some of the medical practitioners. Findings show that phenomena in each of the study areas display similar patterns. Some changes in values and practices related to traditional medicine knowledge have been noted. Knowledge about traditional medicine and their uses is something that is really expected by people due to lack of health centers such as hospitals, clinics and pharmacies, particularly in the remote areas [11]. Among the older generation, skills and knowledge in healing diseases can elevate a person’s status in society (Tarpilih 2010, personal communication, June). Traditional knowledge can be obtained either by study or inherited from previous generations who has been practiced this knowledge to cure diseases for long time ago [12].

i. Traditional Medicine Practitioners by Age

| Age (Years) | Frequency | Percent |

| 40-50 | 3 | 12.9 |

| 51-60 | 7 | 30.1 |

| 61-70 | 5 | 21.5 |

| 71-80 | 5 | 21.5 |

| 81-90 | 3 | 12.9 |

| Total | 23 | 100.0 |

*A total of 23 informants were interviewed

Traditional knowledge about medicine is continuously preserved by successive generations. Great efforts are made, especially by parents, to ensure that this knowledge remains in the family and community. Two tested methods of conserving are through oral teaching and practical experience [13]. Children are encouraged to go with parents when they go to the practitioner to get medicine or receive treatment. Most of the informants agreed that the frequency with which they accompanied their parents on these visits enhanced both their knowledge and confidence about traditional medicine. According to (Teraib 2010, personal communication, January) and (Dayang 2010, personal communication, June), in term of inheritance and the learning process, bringing children to the field is more effective than oral teaching. In previous generations, children were never stopped from participating in healing activities. Table 1 shows that the age of all informants involved in this research is 40 years and above.

In the past, practitioners’ family members relied exclusively on traditional medicines to cure illnesses. However, such medicines were also important aids to personal hygiene and beauty [14], as well as being used to promote spiritual and psychological wellness [15]. Figure 1 shows a traditional hair care product used by medical practitioners in Limbuak Darat village, Banggi Island.

ii. Traditional Medicine Practitioners By Gender

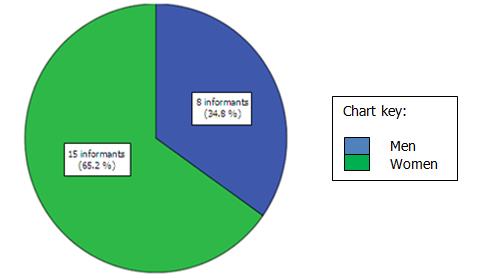

Azmi [15] found that in Lower Kinabatangan, traditional medicine is most frequently used by elders and women. Supporting this contention Figure 2 shows that 65.2 percent of traditional medical practitioners are women: they usually use plants and herbal medicine during pregnancy, after childbirth and to treat child complaints. (Mesiah 2010, personal communication, January) from Limbuak Darat village on Banggi Island said “I have used traditional medicines since my first baby about 20 years ago”. She is still using it today and her confidence in the power of traditional medicine remains equally strong.

|

| *A total of 23 informants were interviewed |

| Figure 2: Medical practitioners* by gender |

iii. Taboos and Change in Traditional Medicine Practices

Traditional knowledge in medicine has its own taboos [15]. In order to ensure the effectiveness of this medicine, medical practitioners need to have some knowledge of the taboos complied with by the patient. A person who is suffering from skin disease for example, should not take prawn, crab, meat or spicy food. When knowledge is passed on to the next generation, practitioners also reveal what they know about medical taboos. Although many medical practitioners believe that traditional medicine is effective in curing diseases, they would also concur with (Awang 2010, personal communication, June) from Binsulok who said, “Compared to our experiences a long time ago, nowadays modern medicines like tablets and pills are easier to get and are used rather than our traditional medicine”. This statement mirrors the opinions of some practitioners of traditional knowledge-based medicine [16]. Even though they actively use traditional medicines, they do not reject the views of the younger generations who prefer modern medicines that are easier to obtain and use. This phenomenon is associated with shorter periods of involvement with traditional medicine practices. Typically, higher degrees of compromise in using modern medicine are among usersofless than 20 years. Period of informants involvement are shown in Table 2. Seven practitioners, representing 31.8 percent of informants, have been using traditional medicine for less than 20 years.

| Years of Involvement | Frequency* | Percent |

| 10-20 | 7 | 31.8 |

| 21-30 | 2 | 9.1 |

| 31-40 | 5 | 22.7 |

| 41-50 | 3 | 13.6 |

| 51-60 and above | 5 | 22.7 |

| Total | 22 | 100.1 |

*A total of 22 informants were interviewed

Today, it is undeniable that traditional medicine practices are in a state of change. Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that socio-economic development is the main reason for this. Factors such as the construction of hospitals and village clinics, the enhancement of educational facilities and markets, religious conversion and land development have led to a decreased dependence on traditional medicine. Essentially, these factors have affected the practice of traditional knowledge either directly or indirectly.

The reduction in the number of users of traditional medicine is due to the increasing attachment of the community to modern medicine. (Tarpilih 2010, personal communication, June), admitted that the marketing of modern medicines at shops and clinics in their village had resulted in the younger generation’s preference for tablets and pills over herbal and plant remedies. Most of them have no confidence in the effectiveness of traditional medicine. (Tarpilih 2010, personal communication, June) states that his children do not want to be treated traditionally because they don’t believe that its works. The same experiences are reported eslewhere. Only in certain circumstances, such as a medical emergency, would young people agree to be treated traditionally (Teraib 2010, personal communication, January). Since they do not rely on traditional medicine, the current generation has no desire to learn its secrets.

The study found that the reluctance of the younger generation to use traditional medicine is not merely because of its perceived ineffectiveness, but also because of the time taken to produce it. Some of the medicine’s ingredients can only be obtained far from residential areas, for example, in forests and near rivers. The bad condition of roads and the lack of facilities have dissuaded people from collecting medicinal plants from their natural habitats. In response to this problem, some practitioners are cultivating medicinal plants in their gardens and courtyards. (Mustara 2010, personal communication, June) Figure 3 is of a potted medicinal plant and was taken at Limbuak Darat village.

iv. The Sources of Plants and Herbs for Traditional Medicine Practices

Table 3 shows that medicinal plants and herbs are regularly taken from forests by 11 of 18 informants. Additional resource areas are garden compounds, the village and surrounding areas, riversides and swamps. Only one informant bought medicinal plants and herbs from the market. This is compatible with the finding that none of the practitioners buy the ingredients for their remedies [16]. Generally-speaking, in comparison with modern medicine, traditional alternatives are only effective with prolonged use. This has undoubtedly been a factor in turning young people away from traditional medicine.

| Sources of Medicinal Plants and Herbs | *Informants Opinions | |

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Retrieved from the forest | 11 | 61.1 |

| Planted around the house | 9 | 50.0 |

| Grow the village | 8 | 44.4 |

| Grown near the river | 7 | 39.0 |

| Planted in the garden | 4 | 22.2 |

| In the swamp area | 2 | 11.1 |

| Purchased from a market | 1 | 5.5 |

*A total of 42 informants were interviewed

In Kalabakan, Nabawan and Sook, medicinal plants have been cultivated in village gardens. Massive expansion of oil palm plantations in recent years has resulted in large areas of land in the Lower Kinabatangan region being converted into agricultural plantations, mainly for oil palm. In order to protect the increasingly endangered swamp forest habitats, the government has designated this area a wildlife sanctuary [16]. The establishment of this sanctuary will be an essential foundation for the conservation of natural forests and it will provide basic protection for wild plants and forest habitats, including medicinal plants. Currently, plants are used by the local community as construction material, firewood, food, traditional medicine and for spiritual uses [16]. One of the side effects of extensive land development is the destruction of the habitats of many medicinal plants.

According to Tongkul [6] owner of traditional forest knowledge face significant challenges, especially encroachment into their lands and expropriation of those lands, leading to forest degradation and the erosion of traditional cultures, values and lifestyles. If disconnected from their natural environments, indigenous communities inevitably lose their traditional knowledge and usually end up among the world’s poorest people. Study by Andersen et al. [16] at the Kuyongon, Penampang showed that primary forest is the most important gathering site because certain species of medicinal plants can only be found there.

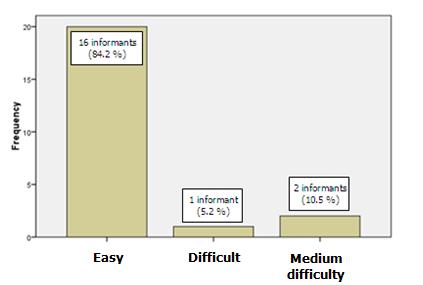

|

| *A total of 19 informants were interviewed |

| Figure 4: *Informants’ opinions on the difficulty of obtaining medicinal plants and herbs |

The same phenomenon was observed in each of the study areas. According to (Mustara 2010, personal communication, June) from the Sukau village, Kinabatangan, oil palm plantation activities have destroyed the habitats of plants used for traditional medicine. Land development has caused some medicinal plants to be replaced by other products which are considered to be more commercial [17]. (Mustara 2010, personal communication, June) admitted that many of the habitats for medicinal plants and herbs have been converted into oil palm plantations. The only means by which inhabitants can get medical plants is by going out into the middle of the virgin jungle. However, Figure 4 shows that 16 informants (84.2 percent) stated that medicinal plants and herbs are still easily available. Similar findings were noted in Binsulok Village, Tuaran. The rental and selling of land as a response to market forces has meant that many people no longer have land on which to grow medicinal plants and herbs. Marketing influences have brought significant social change to these societies.

| Level of Educations | Frequency | Percent |

| Have never attended school | 11 | 47.8 |

| Up to primary school only | 7 | 30.4 |

| Up to secondary school only | 2 | 8.7 |

| Adult education | 2 | 8.7 |

| certificate (e.g. village midwives) | 1 | 4.3 |

| Total | 23 | 100.0 |

*A total of 23 informants were interviewed

What has also been detected in this study is the influence of education on the changing traditional knowledge practices among village members. Table 4 shows that 7 (30.4 percent) of the participants (aged 40 years and above) have only received up to a primary school level of education, whereas 11 (47.8 percent) of the participants have never attended school. (Hussin 2009, personal communication, December) said, “Our education system means that children face time constraints when learning about traditional knowledge. This is in contrast with our childhood experiences, where we spent most of our time learning from the elders about medicinal plants”. Yet, (Hussin 2009, personal communication, December) agreed that writing is important to record knowledge so that it can be retained for future generations. The practitioners’ inability to record their knowledge has had dire effects over the long term. As (Tusin 2009, personal communication, December) acknowledges, “Weakness in reading and writing among elders in our time has made us more dependent on oral and informal techniques of learning”. (Dayang 2010, personal communication, June) reported similarly, “since I was child, this knowledge has never been recorded in written form”. However, the experience was different in Cocos Community, where in order to keep it intact, the inhabitants recorded all their traditional knowledge in a book (Tusin 2009, personal communication, December). Education is an important aspect for retaining of knowledge especially about traditional medicines. But the other constraint faced in recording such information is that some of this knowledge cannot be shared with others due to the need for confidentiality [7]. Recording specialized traditional knowledge is only possible ifthe practitioners are willing to share their knowledge openly.

Although most medical practitioners believe that constraint of time has caused people to abandon traditional treatments, (Razak 2009, personal communication, December) used such practices because of time constraints: “It is easier for me to get all the medical ingredients because we are living in a forest area. But cultivated medicinal plants and herbs near to the housing area are more beneficial”. He began using traditional medicine techniques after he succeeded in curing his eldest child of epilepsy. Difficulties in getting immediate help from the public and the remote location of the house away from medical centers encouraged him to learn about traditional medicine. Razak (2009, personal communication, December) is really proud of one of his friends who has built several treatment centers which practice traditional medicine.

7.3.2 Local Community Participation and the Preservation of Traditional Medicine Practices

Basically, preservation efforts undertaken by medical practitioners in each of the study areas conform to a similar pattern. Interviews with informants indicated that knowledge of traditional medicine had been obtained from parents or other relatives as a result of following them to collect medicinal plants and herbs and through participation in healing activities [18]. Table 5 shows that 20 informants (86.9 percent) inherited traditional medicinal knowledge from their parents and others family members. Self-learning through observation, indirect learning via the experience of being a patient and inspiration from dreams are other sources of knowledge. The level of confidence displayed by practitioners who obtained their knowledge through dreams is in line with medical practices that are often believed to be associated with supernatural forces. Involvement in traditional knowledge practices is however, not compatible with the aspirations of the younger generation. Their disinterest and low level of acquired skills reveals the extent of the retardation of traditional knowledge practices.

| Sources of Traditional Knowledge | Informant’s Opinions | |

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Inherited from family members | 20 | 86.9 |

| Self study | 4 | 17.3 |

| Learned from another community | 3 | 13.0 |

| Obtained through a dream | 1 | 4.3 |

*A total of 28 informants were interviewed

Information from interviews indicates that traditional medicine knowledge is a result of two different types of practice, namely oral and observation. A total of 17 out of 23 informants interviewed (representing 73.9 percent) stated that they acquired their medicinal knowledge by listening to the oral testimony of their parents or grandparents (Table 6). They had also frequently followed their relatives to the plant source areas. A total of 15 informants learnt their knowledge of medicinal plants and herbs through the observation of healings. Only three of them acquired their skills through reading.

| Method of Inheritance | Informant’s opinions | |

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Listening to oral testimony | 17 | 73.9 |

| Through observation | 15 | 65.2 |

| Through reading | 3 | 12.9 |

*A total of 35 informants were interviewed

Besides being a result of the continuing practices of the older generation, the survival of traditional knowledge based medicine has also been influenced by the assumption that traditional medicine can provides cures for diseases that are considered incurable by modern medicine [19]. The interviews confirm that most patients of traditional practitioners are those who were not able to be cured in hospital. Traditional medicine has played an important role as an alternative choice for them. Razak (2009, personal communication, December) claims that some of diseases like santau [12], keteguran [20] and semai [21] cannot be cured by modern medicine. He believes that these types of disease are usually associated with supernatural influences or kesampukan as they are known among locals. Tawar [22] practices used to heal this kind of disease. Most of the patients that said they had been treated are from the practitioners’ village or nearby villages. Table 7 shows that, 20 informants (86.9 percent) acknowledged that their patients came from their own village, while 10 informants (43.4 percent) were treated patients from a nearby village. Only 8 informants (34.7 percent) had ever accepted patients from other districts in Sabah. The common refrain of the patients was that they are suffering from diseases that cannot be cured by modern medicine.

| Patients origin’s | Frequency | Percent |

| From practitioner’s Village | 20 | 86.9 |

| From nearby village | 10 | 43.4 |

| From other districts throughout Sabah | 8 | 34.7 |

*A total of 28 informants were interviewed

Sometimes knowledge of plant and herb-based medicine is applied via a prayer or incantation. According to the interview with (Dayang 2010, personal communication, June) from Binsulok Village, “If a husband and wife or fiancée suddenly experience an emotional episode, and want to get divorced, instead of using medicinal plants, we use tawar to heal the feelings. So many spells need to be recited for that ceremony”. Traditional knowledge about medicinal plants also includes knowledge about the physical and spiritual aspects of nature [7]. Some traditional medicine practitioners believe thatnature hascontrol over the spirit. Therefore, as well as using medicinal herbs and plants, healers sometimes need to carry out spiritual practices such as performingmantras, sacrifices and prayer worship in order to restore the patient.

The abandonment of indigenous animistic beliefs in favour of Christianity and Islam has resulted in contradicting practices among traditional medicine practitioners. Consequently, some practices are no longer observed. Some of the incantation practices of the older generation have been replaced with prayers, especially in the case of the Muslims. Razak from Binsulok said that the Quran and Sunnah are the main resources for him when he performs healing activities. He called this knowledge the Al-Quran method. Findings shows that 21 of the informants (91.3 percent) interviewed are Muslims. Because the traditional knowledge consists of some forms of cultural expression, it also applies to religious and sacred arts, customs and other expressions of faith and ancient beliefs [9]. For example, plants used for medicinal purposes often have symbolic value for the community. Many sculptures, paintings, and crafts are produced based on strict rituals and traditions because of their profound symbolic and, or religious meaning [9].

v. The Inheritance of Traditional Medicinal Knowledge: Inclusion and Exclusion

Due to the prohibiting effect of taboos, the formulas for some types of medication are not allowed to be taught to individuals who have no blood ties with the traditional medicine practitioner. According to (Tusin 2009, personal communication, December) and (Teraib 2010, personal communication, January), traditional knowledge is only passed on freely to the practitioner’s child and wife. If someone with no family ties insists on learning, they must to give a “pengeras” to the medical practitioner(usually a gift or some amount of money). The “Pengeras” acts as a guarantee that the patient will be healed quickly and not suffer from any side effects. Generally, “pengeras” practices can be considered as one of the conservation methods used by the local community to protect their traditional knowledge. Yet, it creates barriers, preventing the traditional knowledge being published in a more commercial way. Gervais agreed that traditional knowledge and intellectual properties are irreconcilable and need to have sui generis protection [9].

Female medical practitioners typically learn about traditional medicine from their mothers. They not only learn how to treat illness but also receive training in how to detect diseases via their symptoms. Dayang (2010, personal communication, June) said, “I learned traditional medicine from my mother. She was among the best disease healers in the past. She always brought me to the jungle and told me things about the medicinal plants. Not only that, she also taught me about the symptoms of diseases”. But among her children, only her second son has the potential to continue practicing her traditional knowledge. Dayang believes that her son has a special instinct. Because of this privilege, even though he has little interest in the knowledge, she always tries to make time to teach him. From this case, it can be concluded that parents are one of the main influences on their children when it comes to their willingness to participate in traditional medicinal practices. The selectivity shown by parents when sharing their knowledge has inevitably hampered efforts to conserve traditional knowledge, particularly in relation to medicinal plants and herbs.

Interviews revealed that some medical practitioners feel more comfortable passing on traditional knowledge to village members than outsiders. As (Samin J 2009, personal communication, December) from Binsulok village said, “Why we should teach outsiders? They are closer to the hospital”. Nevertheless, some informants accept the value of modern medicine while remaining proud of their heritage. Despite practicing traditional medicine everyday their perceptions of modern medicine have changed. Samin J (2009, personal communication, December) one of the more open-minded medical practitioners uses tablets and pills instead of medicinal plants and herbs when traditional based medicines do not seem to be working: “As long as tablets and pills can cure the patient’s disease, that patient can continue to use it no matter whether it is traditional or modern based medicine”. For (Samin J 2009, personal communication, December), diseases that cannot be cured by traditional treatment, must be treated in hospital. For him, “Healing is the goal of all recovery efforts. As long as it can heal, all types of medicines can be used”.

7.3.3.The Challenges to Conserving Traditional Medicine Practices

Difficulties relating to the conservation of traditional knowledge can sometimes be attributed to the attitude of parents. Today, children are overprotected and not required to go to the jungle to collect plants and herbs. This is in contrast to the recent past, when children acquired self-confidence and a sense of responsibility by being allowed to carry out such tasks. They believe that medical preparations can reveal some of medicinal plants to the younger generations. According to (Samin J 2009, personal communication, December), nowadays parents on their own will take the medicines so that they can treat their children and grandchildren. Of his seven children, only the eldest son is interested in learning about traditional medicine. Although he is not able to be a fulltime medical practitioner, (Samin J 2009, personal communication, December), is pleased that this son is able to identify and collect the plants needed to treat his children’s ailments. Spoiling children can result in them getting less exposure to the natural environment, and this can be an obstacle to the conservation of traditional medicinal knowledge. Dayang (2010, personal communication, June) said, “I always remind my son to study very well and not become like me. Doing this job is very tiring and brings fewer advantages”. This statement reveals that parents are also inclined to discourage their children from learning the knowledge because it does not seem to promise any economic benefit.

While (Nurhamah 2010, personal communication, June) from Sukau Village in Kinabatangan said she chose not to sell her traditional medicine or related products. Different findings were reported from Kuyogon, Penampang by Andersen et al. [16]. Even though medicinal plants are almost exclusively collected for household use, but one of the informant occasionally sells medicinal plants at the market. However, selling traditional medicines are sometimes questioned, especially in terms of providing comprehensive medical information to the buyer [18].According to Jantan [23], most of herbal products in Malaysian market are not sufficiently provided with information on their ingredients, indications, dosage, pharmacology, contraindications and possible side effect. This is in line with the situation revealed by Andersen et al. [16] at the Kuyogon, Penampang that the efficacies of any medicinal plants in this area were never been investigates and rarely cross checked. Dayang (2010, personal communication, June) , from Bilit village stated that selling the medicinal products via brochures is a more effective commercially than selling from outlets.

In traditional medical practice, not only the patient, but also the practitioner must show considerable patience. A wide range of ingredients are needed to prepare traditional medicines (Tusin 2009, personal communication, December) and the effects are often slow to materialize compared to modern medicine. (Hamidah 2009, personal communication, December) If a disease cannot be successfully cured, others techniques and ingredients are tried: “It all depends on how the patient’s body responds to the medicine. If the disease is still not cured, we will ask them to come again to try the different medicinal plants and techniques of healing until they are one hundred percent fit” (Hamidah 2009, personal communication, December). Continuous use of these medicinal plants and herbs is one way in which the conservation of traditional medicinal knowledge can be assured.

| Method Used to Disseminate Traditional Medicinal Knowledge | Informant’s Opinions | |

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Not developed/being developed | 10 | 43.5 |

| Instructed to family members | 9 | 39.0 |

| Recorded by family members from afar | 2 | 8.7 |

| Exchanged with others at hospitals,clinics etc. | 1 | 4.3 |

| Instructed to researchers from goverment departments(e.g Forestry Department) | 1 | 4.3 |

| Total | 23 | 100 |

*A total of 23 informants were interviewed

A total of 10 persons (representing 43.5 percent of the informants) admitted that they had not managed to pass on their traditional knowledge to their children, family members and community. At this point in time, no efforts are being made to interest children in the subject. Promoting interest in this field has become more difficult because of the younger generations’ loss of confidence in the effectiveness of traditional medicine. Their trust is firmly in modern medicine. Conservation efforts so far are limited to the passing on of knowledge to family members; and even this has brought only moderate success. To date, no more than 50 percent of the informants have instructed any family members about traditional practices. Some traditional medical practitioners have used a slightly different approach, especially in relation to outsiders. Four of the 23 informants stated that they were prepared to share their knowledge with someone from outside their village. They also gave permission to family members living far from their village to record the knowledge; and allowed them to share it with doctors and patients at hospitals as well as with researchers from government departments. Table 8 forecasts the extinction of the traditional medicinal knowledge if no comprehensive efforts are made to solve the problem.

7.4 CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that currently there are both opportunities for, and threats to, the conservation of traditional medicinal knowledge in Sabah. Increasing land development threatens the habitats of valuable plants and herbs. Due to the better standard of education, more people are aware of the uses and availability of modern medicines (which can now even be obtained from retail stores in rural areas). The practice of passing on traditional knowledge from one generation to the next has not been effective in preserving this rich heritage. In addition to strengthening the older generation’s approach to conservation, new strategies are needed. Current trends and the interests of the younger generation must also be considered. One method of conserving the knowledge is through recording the knowledge via documentary films and books. However, sacrifices and adjustments will need to be made by the medical practitioners if these efforts are to bear fruit.

Traditional and scientific knowledge can complement each other by providing a collaborative sharing of information to support knowledge construction. [5][8] Therefore it is very hard to decide with accuracy which communities are the rightful owners of certain knowledge or the relationship between traditional knowledge and different communities [1]. Sometimes, due to the similar development or due to the exchange of knowledge, communities with related ecosystems, cultures or problems can have the same or similar traditional knowledge which in turn is or is not expressed in a similar fashion [1].

Clearly, intellectual property rights, in particular copyright can be used to protect several forms of traditional knowledge [9]. With respect to tangible property, aboriginal people have property rights that can be transferred and used like most other rights. For example, a specific form of protection for tangible traditional knowledge in the United States is contained in the Indian Arts and Crafts Act (IACA). The Act provides inter alia for the issuance of certification marks through the Indian Arts and Crafts Board. The Act was referred to as a “paper tiger,” since no prosecution has been attempted until 1998, and no conviction has yet been secured. This has been blamed in part at least on the unsuccessful to adopt implementing regulations in a timely manner [8]. A more comprehensive effort is needed by all parties to conserve traditional knowledge on plants and herbs-based medicine so that it can continue to be of use to the whole community.

7.5 REFERENCES

- O’Connor B. Protecting traditional knowledge: An overview of a developing area of intellectual property law. p. 1-41. Available from: http://www.oconnor.be.

- Bodeker G. Indigenous medical knowledge: The law and politics of protection. Paper presented at: Oxford Intellectual Property Research Centre Seminar; 2000 Jan 25; St. Peter’s College, Oxford. 2000.

- Ma Rhea Z. The preservation and maintenance of the knowledge of indigenous peoples and local communities: The role of education. Paper presented at: AARE Conference; 2003; Melbourne, Australia: 2004. p. 1-15.

- Escobar A. Whose knowledge, whose nature? Biodiversity, conservation, and the political ecology of social movements. J Pol Ecol. 1998;5(1998):53-82.

- Moller H, Berkes F, Lyver POB, Kislalioglu M. Combining science and traditional ecological knowledge: Monitoring populations for co-management. Ecol Soc. 2004;9(3):2 Available from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss3/art2.

- Smallacombe S, Davis M, Quiggin R, et al. Scoping project on aboriginal traditional knowledge. Report of a study for the Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre CRC, Alice Springs; 2006.

- Wenzel GW. Traditional ecological knowledge and Inuit: Reflections on TEK research and ethics. Arctic. 1999;52(2):113-124.

- Gervais DJ. Spiritual but no intellectual? The protection of sacred intangible traditional knowledge. Cardoza J Int’l & Comp L. 2003;467-495.

- Udgaonkar S. The recording of traditional knowledge: Will it prevent ‘bio-piracy’? Curr Sci. 2002;82(4):413-419.

- Christensen H. Uses of plants in two indigenous communities in Sarawak, Malaysia [unpublished dissertation]. University of Aarhus, Denmark; 1997.

- Daud H. Oral traditions in Malaysia. Wacana. 2010;12(1):181-200.

- Intergovernmental committee on intellectual property and genetic resources, traditional knowledge and folklore. Third session. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO); 2002. p. 1-11.

- Shizha E, Charema J. Health and welness in Southern Africa: Incorporating indigenous and western healing practices. Int J Psychol Couns. 2011;3(9):167-175.

- Azmi R. Conservation of the Kinabatangan floodplain, Sabah: Flora, habitats and the role of local village communities. Petaling Jaya, Selangor; 1996. WWF: Tabung Alam Malaysia. MYS 304/95 Project Report. p. 1-29.

- Andersen J, Nilsson C, de Richelieu T, et al. Local use of forest products in Kuyongon, Sabah, Malaysia. ARBEC. 2003;1-18. Available from: http://www.arbec.com.my/pdf/art2janmar03.pdf.

- Bodeker G, Bhat KKS, Burley J, Vantomme P. Non-wood forest products 11. Medicinal plants for forest conservation and health care. Rome: Global Intiative for Traditional Systems (GIFTS) of Health, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 1997. p. 1-158.

- Johnson EN. Traditional medicine for modern times: Facts and figures. [homepage on the Internet]. c2016 [cited 2016 Jul 28]. Available from http://www.scidev.net/global/medicine/feature/traditional-medicine-modern-times-facts-figures.html.

- Selin H. Encyclopedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. p. 1588-1596.

- Yakin HSM. Cosmology and world-view among the Bajau: The supernatural beliefs and cultural evolution. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2013;4(9):184-194.

- Baer A. A biomedical and genetic analysis of the Orang Asli of Malaysia: Health, disease & survival. Corvallis: Department of Zoology Oregon State University.

- Wilson CS. Malay medicinal use of plants. J Ethnobiol. 1985;5(2):123-133.

- Jantan I. The scientific values of Malaysian herbal products. Malays J Med Sci. 2006;4(1):59-70.